Justin Redman, one of Britain’s top superyacht designers and director of industry-leading firm RWD, is gesturing over his shoulder. ‘Toby’s using a marker pen,’ he says incredulously. ‘I’ve never seen that before’.

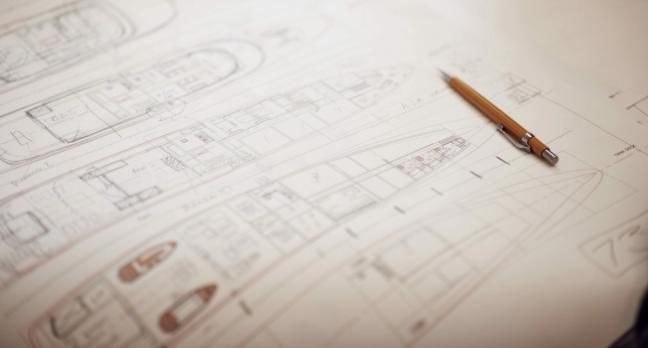

It’s genuine surprise, but then this is no ordinary superyacht design company. Rather than relying on computer programs and ‘cookie cutter’ plans to create boats, every yacht that sails out of RWD begins its life in the tip of a pencil. As such, the company’s design process is as varied and exciting as the vessels it produces.

‘The number of times we’ve had to take scribbled-on tablecloths out of restaurants,’ says Redman. ‘You wouldn’t believe. But we’re always thinking, and talking to our clients, and coming up with ideas at the strangest of times. When inspiration strikes, you draw on whatever’s close to hand – business cards, napkins, backs of envelopes.’

The intimate and intricate process of creating a RWD yacht can take anywhere between three and five years – and is as collaborative as it is creative. Everything from the position of the tenders to the embroidery on the towels is discussed at length with the clients and designed in-house – and this level of detail has seen only 80 yachts designed in the company’s entire 24-year history.

‘If someone came to me and said, ‘Can I have a yacht? I’ll see you at the launch,’ I would be completely bored by that,’ admits Redman. ‘But, like the personal touch that hand-drawing brings, working with them is hugely rewarding for us – and frankly much more fun.’

Ever since RWD left their corporate offices in Chelsea Wharf – instead choosing to drop anchor by a lake in rural Hampshire – the company’s focus has been to create a client experience that is both thoroughly enjoyable and creatively rewarding.

The small, homely complex in Beaulieu – which counts a renovated mill, the old village fire house and a reclaimed jam factory amongst its buildings – often plays host to clients from all over the world. Redman and his fellow designers shoot, ride and fish with the would-be yachtsmen, making the most of the quiet countryside and taking the approach that ideas come more freely outside of stuffy city boardrooms.

‘I always find that by spending time with clients, and asking them about their day, I can find the answers to many of the most important questions we have,’ Redman explains.

If someone came to me and said, ‘Can I have a yacht? I’ll see you at the launch,’ I would be completely bored by that...

‘Tell me about your day?, I may ask. What did you have for breakfast? Did you sit inside or outside? Did you read the paper before breakfast? And, whilst we chat, I’m always sketching, always doodling very early arrangements – and the picture begins to evolve.’

This hand-crafted approach is virtually unique to RWD. Redman acknowledges that computer renderings may be more realistic, but believes that putting pen to paper there and then with a client is both more personal and practical than relying on digital mock-ups. As such, drawing ability is an important part of the firm’s interview process.

‘Most all of us can draw,’ says Redman, ‘because there’ll always be that moment when you need to explain something. Our customer’s time is terribly valuable, so if we can use sketches to make sure we’re on the same wavelength, it’s hugely powerful.

‘And we have all different types of artists here, who each represent their ideas differently. You don’t have to be the next Michelangelo in our line of work – you just have to convey your ideas by sketch. Yes, some will make those drawings a little more accurate in terms of proportion and light and shade, but if you get your idea across by talking and sketching a little at the same time, that works. It’s a communicative tool.’

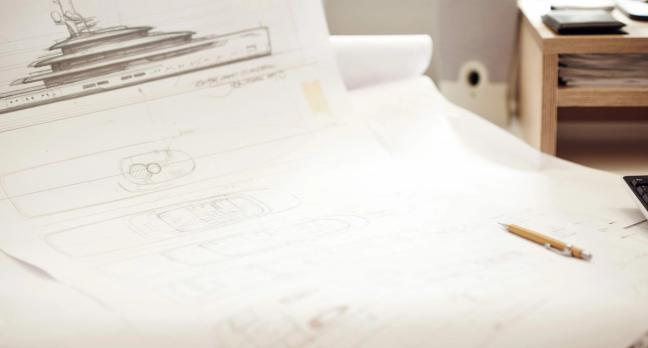

After exploring RWD’s textile department – stacked floor to ceiling with swatches of fabric and slabs of marble – and taking a tour of the communal area in the old mill – complete with wood-burning stove and models of past projects – I visit Creative Director Toby Ecuyer.

Ecuyer, who has stopped making waves with his marker pen, is poring over plans – a Japanese Blackwing pencil now in hand. Books on naval architecture line the walls of his studio, and the designer’s dog sits curled under his drawing board with an aptly naval-print neckerchief tied around her neck.

‘Biro is my failsafe,’ says Ecuyer, setting down the pencil and picking up a pen. ‘If I’m having a bad drawing day, Biro will always get me out of it. It may seem like a commitment, but you get the whole story with Biro. You draw over yourself, yes, but you get all the construction that way, all the other stories.’

Ecuyer, who joined the company in 2004 after cutting his teeth in the world of high-end architecture, understands the importance of the right drawing tool. From pens and pencils to paints, the designer uses a combination of techniques to design – a fact to which bulging binders of oversized A2 and yellow draughtsmen paper attest.

‘Our clients get to imagine something,’ says Ecuyer, ‘and then see it appear – almost immediately – in front of them on paper. To witness these small collections of lines become a reality is such a rare experience. We’ve made it hard for ourselves, really, because our clients need to be creative in order to see the potential on the paper.’

The biggest yacht RWD has designed so far measured just over 500 feet – so each pen or pencil stroke can translates into millions in building costs. Yet the process begins simply; freehand and without constraints.

Biro is my failsafe. If I’m having a bad drawing day, Biro will always get me out of it. It may seem like a commitment, but you get the whole story with Biro...

‘Drawing is very adaptable,’ says Ecuyer, ‘which is important as our clients are so different. Sometimes I do 180 sketches for a boat – sometimes I do four. And sometimes, the sketches that get the best reaction are those I’ve done very quickly, on the corner of some meeting notes with a little felt tip.

‘The point of these drawings is to evoke an emotion, a feeling or an impression of how it could be – and that’s something the hand-drawn touch really gives you. With watercolours, the paint might go over the edges, but that’s almost on purpose. If you’re too precise, they lose a bit of life.’

Life, like the collaborative relationship between client and designer, is clearly important to RWD. From Redman asking about a customer’s typical day to the small details Ecuyer adds into his drawings, the yachts manage to feel lived-in and full of character before they’re even built.

The Creative Director points at a sketch of an open cargo hold – designed specifically to house two Land Rovers. The view outside the door shows a penguin perched on a chunk of floating ice. ‘I almost did a walrus,’ Ecuyer says wryly.

‘It’s this character that you only get with sketches,’ he continues. ‘And most people love the sketches. Some think that computer renderings feel too final, and as if everything’s already been decided. And I think they’re right, I think you get so much more from drawings. Computer renderings are necessary but, after a certain number of clicks, I think you stop being an artist.

‘You can discuss ideas with a client, but disappear for three weeks to render them, and the moment’s gone.’

Justin Redman pokes his head around the door to agree. ‘That’s why our same personal values persist to this day,’ the Director says. ‘The art of hand-drawing, the intimacy of sitting with someone, sketching, and collaborating on their design. I don’t think there’s a more direct way to do that.

‘People call it magic – and I don’t know whether I’d say that, but it’s certainly a very special thing.’

Become a Gentleman’s Journal Member?

Like the Gentleman’s Journal? Why not join the Clubhouse, a special kind of private club where members receive offers and experiences from hand-picked, premium brands. You will also receive invites to exclusive events, the quarterly print magazine delivered directly to your door and your own membership card.