Is this the end of the high five?

A cultural history (and love letter) to the fading greeting

Here’s a truth universally acknowledged: mums don’t know how to high five. They know how to intellectually, of course. They understand the premise and the aim. They have seen it on The Crystal Maze, or in the mixed doubles at Wimbledon. They nailed it in the eighties, presumably. But at the moment of delivery, the moment of celebration and connection and impact and truth, they always somehow fail. It becomes more of a push than a slap; the hand is too rigid and yet too soft; there is no satisfying clap or yeehaw; there is too much give and hesitation and care; they swing into it with the upper body; they try too hard. Mums are only about seven percent off, but it’s that seven percent that matters. When you’re four, your mother teaches you how to high five. When you’re five, you teach her. And when you’re six, you stop trying altogether. (The trick, by the way, is to look at the other person’s elbow at the moment of striking. And not to overthink it.)

High fives: fine for dogs; tricky for mums

I thought about this again the other day, when I saw my nephew for the first time in months. He is six and conscientious and entirely sweet. In lieu of anything too transmissive, he stuck out his hand into a perfect little fleshy pink fist — you would put it on a menu if you could, and glaze it in Korean BBQ sauce — and gave me a gentle but purposeful tap. One of the most boring cliches of the pandemic is that it has ‘accelerated trends that were happening anyway’, like working from home or thinking celebrities are actually quite irritating or growing out your mullet. But in the case of greetings I think it’s certainly true. Suddenly, in a pique of that swirling panic that always comes with the reminder of your own age and the zooming passage of time, I realised that my nephew was the product of a separate era entirely: generation fist bump. Yes, he would always be aware of the high five in the canon of casual greetings — those occasions when a handshake is too backward and a hug is too forward. But the fist bump would now be the go-to procedure, leaving its open-palm relative in some Blockbuster Bargain bin of Gen-X irony and Boomer over-exuberance. Too germy and sickly, sure. But also too try-hard and tricky, which is worse. Pandemics pass. Ungainliness rarely does.

"His hand was up in the air, and he was arching way back," says Dusty Baker. "So I reached up and hit his hand..."

It is hard to imagine it now, but the fist bump hasn’t always been with us. I was first taught the trick at the age of 10 by a large boy on our street who owned a BMX and a Korn hoodie and was good value at car boot sales. It felt deliciously illicit and teenaged, like Dr Dre CDs and BB guns, with the nauseous tang of what might now be called cultural appropriation. When, at the turn of the millennium, Ali G foisted a fist bump on politicians or establishment grandees, they would awkwardly attempt to grab at it, or tap it open-palmed, or manfully shake it regardless. He did the trick on Boutros Boutros-Ghali, and a young Jacob Rees-Mogg (an oxymoron), and many others, and it was always the physical punchline to his wider interview schtick: new and ‘urban’ and edgy and exotic and revealing. The Secretary General of the UN could handle a high five, but a fist bump was fresh hell.

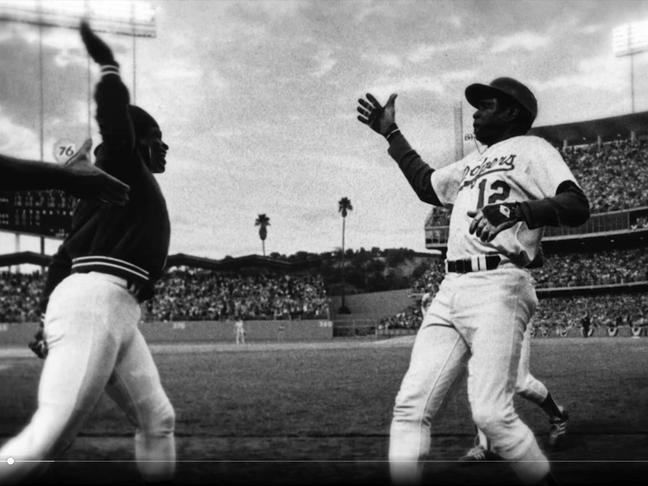

Los Angeles Dodgers players Glenn Burke and Dusty Baker pull off what some say is the first-ever high five, 1977

Then came a period of creeping middle class adoption across the noughties — a sort of knowing, happy-slapping, Little Britain, aren’t-we-fun absorption — until the fistbump became the go-to sporting celebration in both doubles tennis and cricket, among others. (They do it with two fists up, the fleshy heels of their hands meeting with a purpose. This may be its most pleasing form.) Even in the ‘old normal’, it was a useful common currency — something you’d give to a seated table of acquaintances in a pub garden when hugs were ergonomically impossible; an act of drunken goodbye to the Uber driver who doesn’t care about your life story but who is contractually obliged to listen and nod, at least until we get back to Fulham. Unlike the high-five, the fistbump works at all angles and in all spaces — there is no need for height parity or swinging room.

The sporting shift is significant, actually. The high five has several competing origin stories, but they almost all take place in American athletic arenas. Basketball legend Magic Johnson claimed that he invented the manoeuvre while playing at Michigan State. Others say it originated on the women’s volleyball circuit in the 1960s. The longest held theory pins the invention to October 2nd 1977, and Los Angeles’ Dodger Stadium, when left-fielder Dusty Baker hit a magnificent home run. As Baker rounded the corner on his victory lap, he passed teammate Glenn Burke, who had his arm held triumphantly aloft. “His hand was up in the air, and he was arching way back,” says Baker. “So I reached up and hit his hand. It seemed like the thing to do.” A more recent thesis maintains that the first high-five took place during a University of Louisville basketball practice session in 1979. Forward Wiley Brown went to give a traditional low five to his teammate Derek Smith, when, as if possessed by some divine inspiration, Smith looked Brown dead in the eye and said: “No. Up high.” This is confirmed by archive footage from that season, when the Cardinals can be seen doling out their prototype high five — slightly clumsy, charmingly un-finessed — after each score, while a newspaper report in the New York Times the next year talks about this exciting new fad and names Louisville as its birthplace.

From there, it seems, the craze spread like a virus (if that’s not too sharp an analogy), transmitting via America’s growing soft power, the dominance of MTV culture, and the rise of international sports coverage. By the mid-eighties it was a playground staple. By the nineties, it was drenched in irony, just like everything else. By the noughties, it was on the way out. It will be interesting to see whether the current wave of mid-to-late nineties nostalgia (Sex in the City returning; the Friends and Frasier reboots) will bring the manoevure back at all. But in general, you sense that the party is dwindling, and the golden days are behind us. You do sometimes see the high five on sporting pitches nowadays, but it’s much rarer, and is mostly double-handed and grabbing and sweaty; a preface to a rugged embrace. (And even this, you’ll notice, is technically a high ten).

In March, a book by Ella Al-Shamahi hymned the cultural significance of the handshake, and urged us to revive it in a year when it came to be seen not as a greeting but a biohazard. Like the high-five, the sheer palminess of the handshake — and the threat of moist softness and cloying warmth — has always lent it an air of contagion. Donald Trump famously hates handshakes, and not just because he has tiny hands. Once, when asked “May I shake the hand that wrote Ulysses?”, James Joyce replied: “Certainly not. It did other things as well.” But Al-Shamahi makes a good case for the handshake’s revival post-pandemic, painting it as a uniquely poised act — friendly and formal at once; intimate but never sexual. Other greetings are vanishing too: in a village in Papua, western New Guinea, Al-Shamahi explains, you say hello with “a brief ‘welcoming suck’ on the breast of the chief’s wife”, but apparently this is on the way out. The handshake, however, is worth preserving, she says — not just as “a learnt cultural tradition” but as “something deeply biological in origin”.

"The barriers are lowered and the guard is down. There are no egos around a bungled high five."

Perhaps one day someone will make the same case for the high five. It seems to me worth holding on to for a few reasons (nostalgia for a simpler time; sporting exuberance; the pleasing noisiness, where most other gestures are silent). But most significant, perhaps, is that maternal ungainliness. In fairness to my mother, high-fives are tricky and prone to mis-fires and often awkward. But this brings a bonding element all of its own — the unique ambience of the fancy-dress party. We know we might look a little foolish, but we’re all in it together. The barriers are lowered and the guard is down. There are no egos around a bungled high five.

There is hope yet for the manoeuvre. This may not be a zero-sum game, after all. I asked my nephew which he prefers: the fist bump or the high five. “People aren’t doing either at the moment,” he wisely points out. But when they return, he reckons he’ll dabble in both. After all, “fist bumps are friendship,” he says. “But high fives are teamwork.”

Read next: In defence of stolen ashtrays

Become a Gentleman’s Journal Member?

Like the Gentleman’s Journal? Why not join the Clubhouse, a special kind of private club where members receive offers and experiences from hand-picked, premium brands. You will also receive invites to exclusive events, the quarterly print magazine delivered directly to your door and your own membership card.