Jann Wenner, founder of Rolling Stone magazine, turns back the clock

Rolling Stone magazine didn’t just write about rock and roll. It was rock and roll — a heady swirl of huge characters, big money, and psychedelic excess. At his home in Manhattan, its talisman remembers the Beatles, Hunter S Thompson, and the golden age of magazines…

“I don’t regret life,” says Jann S Wenner as he walks through the rooms of his vast, handsome townhouse on the Upper West Side.It is a hot day in mid May — hot for an Englishman, at least — and when I’d arrived, an hour or so earlier, Jann had opened the double front doors himself, so you walked straight into the story. We were there to talk about his newish memoir, out in June in paperback, and I probably didn’t need to come all this way for a 90-minute interview — to stump up for the flights, wrestle with the accountant, beg for the freebie hotel room, schlep dazed from JFK, and dodge the construction work that appeared to be angrily gobbling half of Manhattan. But Jann had promised lunch, and white asparagus with grilled mackerel tends to lose something over Zoom.

So might Jann Wenner, I suspect. To interview the founder of Rolling Stone magazine over the internet would be like microwaving your coffee, or playing Debussy through an iPhone speaker. The man pioneered the sort of long-form, intimate, deeply analogue interview that modern writers — in an era when magazines are sometimes described simply as ‘dead tree media’ — weep over in the still of the night. He was the ruler of a lost kingdom: a time long before helicopter publicists and junkets, back when staff writers would do three days with their subjects and three grams with their subjects, and people would actually read the thing afterwards and talk about it, and nobody would get angry on Twitter about things that nobody else had really said.

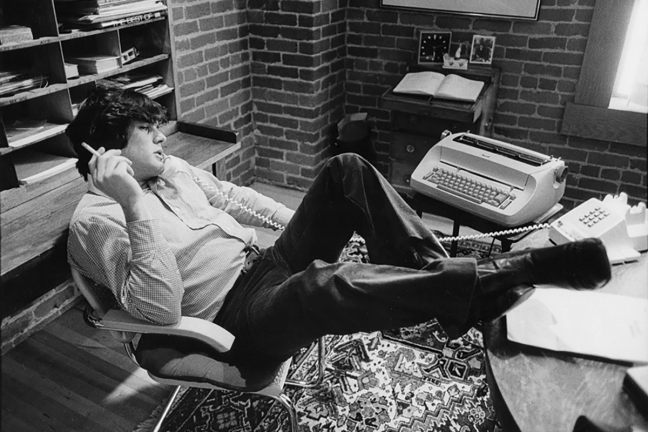

Jann Wenner in Rolling Stone's San Francisco office, 1975

There’s no cocaine today, mind you, just two glasses of ginger ale tinkling with ice, served on a big, wide sofa below a gilded relief from a 14th-century French church in the light-filled drawing room where we’re sitting. In another room just beyond us, eight Warhol prints of Chairman Mao hover airily over a smooth, round wooden table that Jann used as a desk for years, he says, and it was looking up at the chairmen that he’d chuckled about not regretting life whatsoever, thanks very much. To someone who works in the media in 2023, the effect of it all — of the ginger ale, the blue-chip artwork, the light — is a sense of being born into just the wrong era; of missing the good times; of arriving at the party once the lights have come on and the music has stopped and the champagne has curdled on the mantel.

Hell of a party, though. A sort of second-hand nostalgia resonates throughout Jann’s deep, rich book, Like a Rolling Stone, even if that nostalgia might sometimes be misguided or misplaced. The memoir is certainly not a catalogue or product of regrets. Instead, its creation reflects another anxiety, which may well be the opposite: a sort of manic optimism and self belief; a sense of impending history and outsized significance. Jann started Rolling Stone magazine in 1967, when he was 21 years old, in the San Francisco of the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane. And from the very beginning, he collected the ephemera and flotsam of daily life — appointment books, postcards, receipts, memos, photographs, commissioning notes — with the mostly unconscious idea that they might one day be freighted with some historical significance.

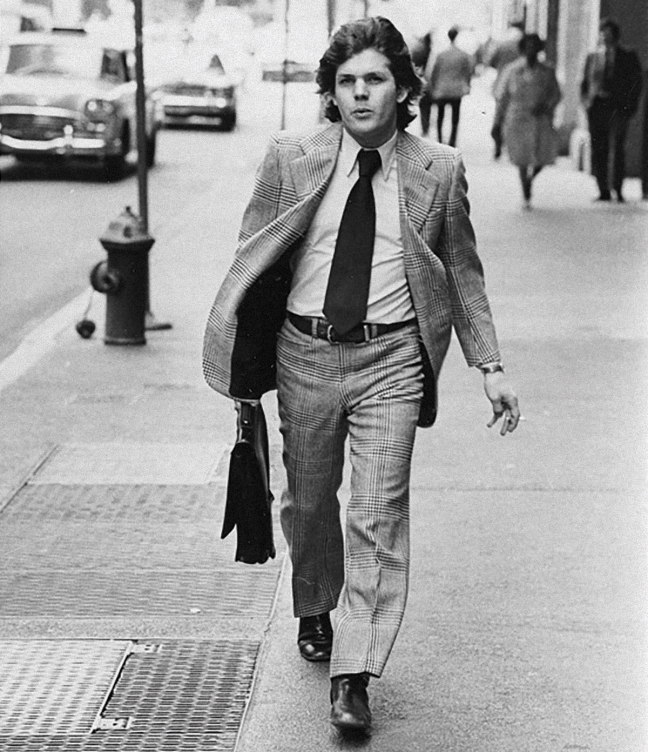

Jann Wenner, on Fifth Avenue in 1977, following the move to New York: “a full-fledged enfant terrible of journalism”

Jann Wenner, with Barack Obama in the Oval Office, 2010

“When I saw some early video of myself, sitting in my T-shirt at my old desk,” Jann says, “and I saw what a cute kid I was, and the energy I had… I mean, anyone would go with that kid. Anyone would buy that.”

The magazine was created to write seriously about the geysering, glimmering culture of rock and roll and everything it entailed — psychedelics, politics, art and community; the blossoming concerns of the biggest generation in history. At some point in its first few years, it stopped simply reporting on the culture and began shaping and orchestrating it too. Cover stars were not really a thing before Rolling Stone, but by 1972 a band called Dr Hook & The Medicine Show had released a hit song in which they begged jokily to appear on ‘the cover of the Rollin’ Stone’ — a reflection of what that pedestal might do for an artist, and what it was doing to the culture. At the same time, Jann moved from writing about the stars of the era to being pals with them (something that’s largely unthinkable today), while the writers on his roster became celebrities in their own rights — Hunter S Thompson and Tom Wolfe, say, who both played amplified versions of themselves on the page and in person, with costumes and props and stunts; living ‘brands’, long before anyone cared to know what that meant.

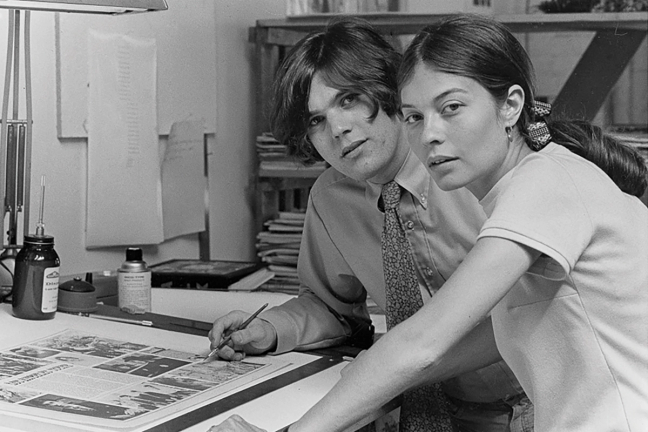

Jann Wenner, with then-wife Jane Wenner in 1968

Rolling Stone could write intimately about rock and roll because it was rock and roll — grappling and cavorting with drugs, excess, art, fame, sex and money, just like the bands it followed. Wenner once shocked a young reporter during an early profile by pouring out and sniffing a huge slug of cocaine mid interview. Annie Leibovitz knew to undo the top button on the jeans of any male cover star she shot. Hunter S Thompson said he’d have the “mind of an accountant” without the drugs. The magazine handed out roach-clips to its subscribers, while the office’s photography dark room became a coke den called the ‘Capri Lounge’ to get writers on deadline through the night. Thompson wrote once that the whole thing was “like being invited into a bonfire and finding out the fire is actually your friend”. Heat, light, noise, fuel and ash. And if Rolling Stone was a band, then Jann Wenner was the front man, the tour manager, the producer, the songwriter, the chief groupie and the critic, all in one.

Artistic integrity mattered. After the events of Altamont in 1969 — the cursed Rolling Stones concert at which a young black man was murdered by hired Hells Angel thugs — a colleague of Jann’s remembers the steely tone of his voice when he told the young team to report it all, in full grisly detail, even if it meant firebombing their burgeoning relationship with the biggest band in the world. But success — subscriber numbers, money, beating the competition, taking on the establishment and eventually becoming part of it — was important, too. “People think it’s better to say: ‘I wanted to be rich from an early age’,” Jann says. “I’m glad to be rich — I enjoy the money. It’s always been better. But it was never my intention — it was totally my love of rock and roll that drove me.”

This combination — of idealism with capitalism, of the kind vibes with the cash — may strike people of a younger generation as akin to Baby Boomer cakeism, the easy shrug of the generation that had it all and had it easy. That’s not to say that it was simple, of course — and the manic, talismanic energy that Jann mustered over the years to keep the magazine going looks frankly exhausting in any era. But if you could almost have it all, why wouldn’t you try? In the late 1970s, when Jann moved the Rolling Stone offices from San Francisco to New York, and befriended Jackie Onassis and courted Madison Avenue, people began to whisper that he had sold out. In reality, he’d just grown up, if only a little. An old joke that’s repeated in the book is how the 42-year-old Ralph Gleason, the jazz guru and mentor of Jann who helped him set up the magazine, couldn’t decide if he was two 24-year-olds, three 16-year- olds or four 12-year-olds. There’s a similar thing going on with Jann, with his slate-grey hair spiked up over a puckish face and mischievous smile. Over lunch in his courtyard garden, filled with acer trees and pink flowers, he is by turns ‘avuncular’ (his word) and conspiratorial — checking up on what contemporary American authors I’m reading, but also gossiping and cajoling and riffing as if in some way I’m the prim and elder stick in the mud, and he’s the rebellious younger brother.

“There was alienation from society, but also joy, hope, freedom. We were educated in both...”

Rolling Stone’s highlights reel is well known and well worn, snaking through the highs and lows of the end of the 20th century. The magazine won awards and acclaim for its coverage of the Manson Family murders, the Patty Hearst saga, its early addressing of global warming and the unfolding AIDS crisis. In December 1980, Annie Leibovitz shot the magazine’s most famous cover image, of a naked John Lennon curled up next to a clothed Yoko Ono. Hours after it was taken, Lennon was shot dead outside his apartment in New York. When Wenner went to meet Ono just after the murder, she is said to have placed Lennon’s bloody glasses into his palm.

Jann Wenner, with Bill Clinton aboard Air Force One, 2000

There were in-depth eviscerations of Nixon and George W Bush; intimate cover interviews with Bill Clinton and Barack Obama. It is telling that one of the most ‘painful’ moments Jann felt when revisiting his career was a serious journalistic snafu — the 2014 story A Rape on Campus, about a frat-house sexual assault case at the University of Virginia, which, it soon became clear, had been almost entirely fabricated by its alleged victim. The oversights involved in the bungled story were perhaps indicative of the waning journalistic heft of the magazine, in an industry which has been flayed by a financial crisis and the coming of the internet. One of the most poignant passages in the book comes at the very start, where Jann describes his final day in the Rolling Stone offices, in May 2019. “Within a few days, workers would be tearing apart the private office where for nearly 30 years I had lived and ruled, achieved fame and fortune. When I walked out that last time, I left numb. As Hunter would say, I see buzzards circling overhead.”

Jann is still an editor at heart, though he sold most of his stake in the magazine in 2017, following a femur snapped on the tennis court and a subsequent heart attack. (Nowadays his son, Gus, runs it. Earlier this year it was reported that Rolling Stone had had its most successful financial year in ‘two decades’.) Jann asks me, when we sit down, what I “really want out of this piece” and later, when I am discussing using some portraits from the book with him, he advises me to “run the Annie shot over the gutter.”

What I really want, I say, is largely selfish and closely tied to my own job — just to sort of feel, second-hand, the texture of life in those times for someone who made magazines, and shaped the idea of magazines and of journalism. I’m not interested in scoops or gotchas in a way that a tourist on a safari presumably doesn’t want to shoot the elephant. I say that there’s a line from Joni Mitchell’s song ‘California’ playing in my head, which feels baked with the sunlight and optimism and good times of another place and era. (Though not necessarily a simpler era, as Jann points out — “there was alienation from society, but also joy, hope, freedom. My generation was educated in both”.) ‘Went to a party down a red dirt road/There were lots of pretty people there/Reading Rolling Stone, reading Vogue,’ it goes and, apparently, it’s about a bash Jann held at a house in Ibiza in the late 60s. In that lilting verse, freedom and youth and summer and revolution are indistinguishable from the pretty people and the magazines they read. Those worlds were each swoonily, merrily intertwined, and Jann was often right in the middle of them all. I ask him at the end of our conversation whether he has a motto, and he says, with a little tinkling wave of the hand, that he often finds himself saying simply “have fun” to people he knows and loves. Alongside everything else, the great success of Jann Wenner is that he did, and that he does.

Jann Wenner, sailing with Mick Jagger and Earl McGrath, Mustique, 1985

JB: California seemed to be a particularly fertile creative place when you were starting out. What do you remember about that time?

JW: It was youthful and full of the promise of youth and the exuberance of it, and of the freedom of the time — the beauty of the land, and the fruit of the land. It’s rich soil.

Beautiful is a good word to use, because youth is beauty. I was a good-looking little kid. I was a cute kid. There is a kind of beauty in that age, the early twenties — a beautiful period of life. We were naive, yes, in many senses — and in other ways very thoughtful and very sophisticated about life and what it was supposed to be about. It was an age of hope and great cynicism. I started the 60s with the killing of a president. I was just a freshman in college. I was born in ’46 — the leading edge of that generation. That was my first experience: the assassination of this wonderful, golden man. He spoke so eloquently, so beautifully, with hope. You think, “‘God, had he stayed…”

This was the new America. And we were ready, young, educated, wealthy — the pride of the nation, primed for life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. And then what happened to us was that our hero president was assassinated. And then there was the war in Vietnam, and all you learned was how horrible the government was, how untrustworthy and evil the adult generation was.

They killed Bobby Kennedy, killed Martin Luther King. Riots. Nixon. That’s what happened to our generation. But, at the same time, there were other aspects — The Beatles, the Stones, Bob Dylan. So there was alienation from society, but also joy, hope, freedom; the way to live; the proper treatment of your fellow man. That generation was educated in both.

What was the magazine world like back then?

JW: At that time, when I started, magazines mattered. They were one of the most important mediums around. Magazines defined for people a way of life. Even things like Guns & Ammo —that was a way of life. So you can imagine what Rolling Stone did — it said who you were, and what your life was like, and it was very important to your world view. We helped people define their lives and define the time.

That’s not the case anymore.

JW: I’m sorry to say magazines mean nothing today. The great magazines that were my contemporaries, there are fragments of them left — but Time magazine means nothing. Vanity Fair means nothing. The New Yorker’s still got a little something — but even that’s diminished. The whole magazine world has shrunk. There’s not enough water in the lake.

They don’t have the time to do what we did. To take two to three months on a piece, and go write it carefully and thoughtfully. That’s what made our work so important. Now, the information environment is so broad, so vast, so deep, it’s unnecessary to have a long take on anything. You piece it together yourself. [By the time the story is happening] you’ve figured it out already.

And if not, AI is tomorrow. So that’s it.

Rolling Stone still has a certain aura…

JW: Rolling Stone still exists, but it’s a different thing now. It tries to cover some of the same territories, and observe some of the same conventions and styles, but it has eviscerated its artistic and creative staff. They’ve let go of people who were too expensive, and told the rest to write online now. Is the Rolling Stone cover meaningful anymore?

My son still runs it. And they do a good job. But it’s the climate around it — they don’t have the luxuries I had. We had money, we had a lot of profits, so we could do what we wanted to do. They don’t. The times are different.

It’s got a lot of presence, it’s got a lot of identity. I think they’ll try and revive it again and put more money into it. I don’t think they want to give up on that magazine. It’s still got just a tremendous identity, or ‘brand’, as they say these days.

“I’m sorry to say that magazines mean nothing today...”

What did you want to be when you were growing up?

JW: I had no idea what I wanted to be. Rolling Stone journalism was the default for me. I thought rock and roll should take over the world, and that we’d have a million circulation overnight — without knowing what the fuck that meant. I had no clue about marketing, or success, or what that would look like. I was a rock and roll fan. I played a little music, but it wasn’t my thing. You know what they say: if you can’t do, teach…

Did you have big ambitions from the start?

JW: People think it’s better to say: “I wanted to be rich from an early age”. That’s the value system of today. But it was never my motive. I’m glad to be rich — I enjoy the money. It’s always been better. I was raised next to rich people, so I knew what it was like. But it was never my intention. It was totally my love of rock and roll that drove me.

I was relatively grown up in some way. I was serious. I did things at high school that the serious kids did, and I took politics seriously. But in other ways I was enjoying a life of loving abandon.

Do you still feel young now?

JW: I don’t feel like Jann at 22. But I feel young at heart. I think that’s true of all the people I know. I think it’s good for all kinds of reasons. It’s a healthy outlook on life. It’s partly because the Baby Boom generation was so large and so dominant, so there’s a sense of Baby Boomers forever being young.

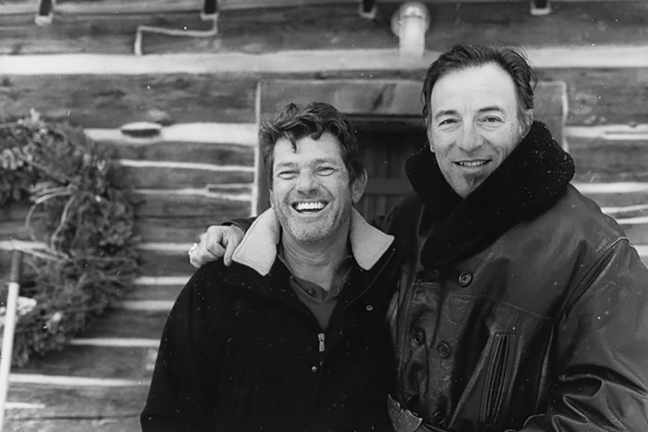

Jann Wenner, with Bruce Springsteen

What did you learn from your parents?

JW: I got my mother’s skill and talent. She was a writer and an editor, and musical and political. My dad was a businessman. It was embarrassing to me explaining to people at that time that he was in baby formulas. But he was an entrepreneur, and a wise man. He was smart about everything, and knew why things worked, and he could explain it. I think I have a bit of that in myself — the ability to take a larger view of things, and understand things, and explain in simple terms why things are the way they are.

What kind of people did you hire at Rolling Stone early on? I’ve heard that in your job interviews you would ask people what sort of drugs they took…

JW: I didn’t want to hire someone who didn’t believe what I believed, or didn’t have the sensibility to execute this very specific thing. There was something very important about drug culture and consciousness. There was a unique kind of view of things, which not everyone had. It was a level of awareness. I don’t want to make too big a deal of it, but that was important then. Now, it’s just about skills.

Were psychedelics important to the outlook and sensibility of Rolling Stone?

JW: Yes, absolutely. They gave you a sense of who you were in relation to the world, and a very critical understanding of your shared humanity, and your responsibility to other people and the life around you and the plants and forests — an awareness that everything was interconnected and needed to be treated with respect and care and love. And from that consciousness you had to proceed to make your decisions in life. That benchmark was very important, and was reflected in rock and roll.

Do you take psychedelics now?

JW: That would be my business…

You met a lot of your heroes. Who most subverted your prior expectations?

JW: The one that was most surprising was John Lennon, because he was straightforward: no bullshit, no airs, no fancy shit. Obviously, not a regular person, but he just didn’t have any pretence about him. He was who he was, and that made it easy to deal with him. He shot his mouth off without restraint, and you felt you could do the same. There were no barriers there. Everyone else came with some barriers: Mick, Bob. John didn’t. He came with defences against people he didn’t know, but in my experience it was all straight shooting.

You’ve been very close to fame for decades. What do you think of it as a force?

JW: Fame can be very destructive. You really have to be very careful. It’s destabilising and disorientating and debilitating, and you have to have some strong roots and good people around you. And drugs don’t help. Drugs in general can lead to some bad results…

You are fairly well known yourself…

JW: I’m not a rock star. But there’s wonderful things about the gratification of people coming up to you and saying they appreciate your work. There’s a wonderful thing about being able to get a table at a restaurant any time you want. That’s the best thing about being famous.

It can be intoxicating if you’re on stage and performing, however. There’s something about that act. It’s the sound, the approval, the looks — it’s physically intoxicating because it moves your adrenaline so high that that takes you over. Otherwise, as I said, it can be very distorting. You get weird. Do people like me for me? Even at my low level, maybe people like me for other reasons. But it’s an occupational hazard. You get used to it.

How did you juggle the excess of that era — the drugs — with the other elements of the job?

JW: In that era, there were drugs all over the place. People hadn’t quite gotten the understanding of them they needed to get. Cocaine was still supposed to be good. People had not wised up to the serious consequences of some of these drugs, just as they hadn’t wised up to smoking. Cocaine was everywhere, and the word hadn’t got out yet of what it could do to you with long-term use.

It was a juggling act. It wasted a lot of time and effort. I could juggle it. But in the end not that well. It has its price and its cost. I had good times with it, but I might have moved things along twice as far, had I not wasted so much time taking drugs.

Some artists and creatives say that the drugs are a crucial part of their process, their success…

JW: I think it is bullshit. Hunter said that had he not taken drugs he would have had the mind of an accountant. But in my experience, I can’t say cocaine benefitted anybody’s productivity. I can think of pot enhancing someone’s productivity. And I can think of LSD tremendously enhancing your productivity. But not cocaine. That was a waste of time — no good. And I denounce it in my book. I openly say, if I could take it back, I would.

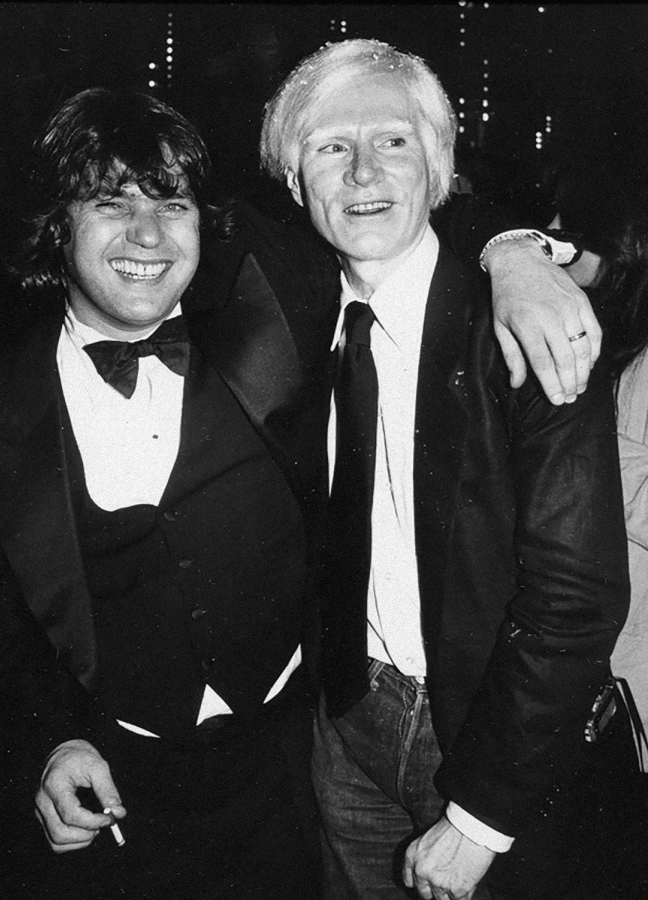

Jann Wenner, with Andy Warhol

When you describe Hunter S Thompson in the book, coming into the office with a bag of tricks and props, it is like he is a character; like he’s playing a role…

JW: In part, but they were one and the same. When it started to become a character, that was the time Hunter started to lose his talent and skills. But he was fun. He was a little boy. He liked pranks, and buying joy buzzers — he loved that shit.

Hunter gave people a feeling that you were going to get as close to the edge as you were ever going to get. That this would be the craziest, most fun, most extreme, most drama-filled night of your life. Talk about luck. To have all that time with Hunter. I can see him walking in here today. He is as vivid in my imagination and in my life today as he ever was.

Was it a shock when you heard he took his own life?

JW: It wasn’t a surprise. It wasn’t something that didn’t compute. But it was devastating. It was devastating for a long time. There was something indelible… I loved Hunter. I didn’t worship him, but he was so mad and special to me. I don’t know.

What is Annie Leibovitz’s particular genius? Why is she such a good photographer?

JW: I didn’t understand how she’d get someone sitting on a couch or a bed, looking at you and the camera, and it was like a real moment where you felt you got to know them as if you were sitting right there. She has a penetrating look and an intimacy. And that eye also has to work outside the camera in the studio and retouching. But, Jesus, she’s the greatest living photographer in the world.

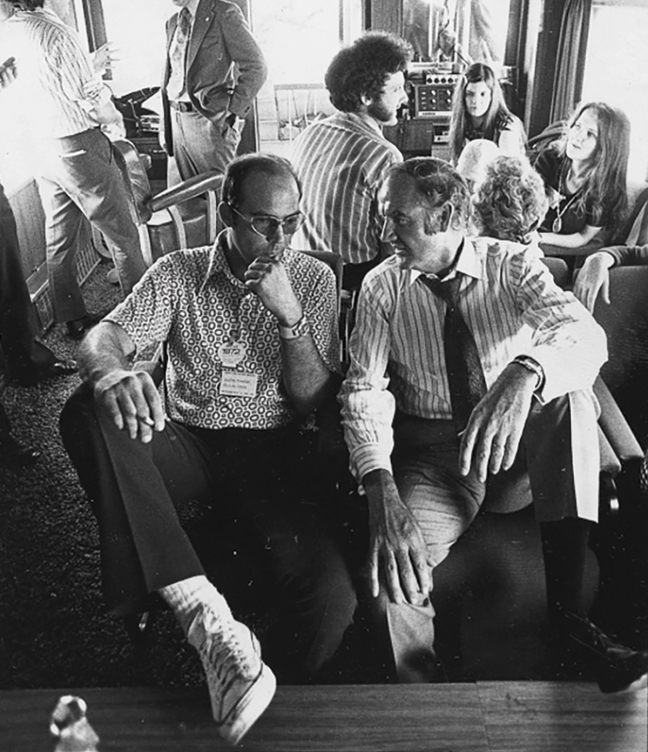

Hunter S Thompson and Senator George McGovern on the presidential campaign trail, 1972

The book is so rich because you kept such meticulous records throughout your career. Did you have a sense of posterity, of history, from the start?

JW: I didn’t have any conception of it or formalise it. I just knew that this was good stuff. Since I was a little kid, I was saving all this stuff from my parents. It’s all in storage, in an archive. But I always saved everything. I had some sense that what I was doing was going to be important. I don’t know why.

You worked with the writer Joe Hagan on an earlier biography…

JW: I had wanted someone else to write it. I was too lazy. I thought Joe Hagan would be good at it, and it was serendipity that I ran into him. But in my view it was not good. It was a disaster and a disappointment. It was badly done.

Then I had a heart attack and sold the company and all of a sudden I had the time. I was forced to write it because I needed something to do.

I wasn’t just going to sit around here. It was three years of work. I didn’t write it to rebut Joe Hagan. One of my goals had not been satisfied by that book, so I had to do it myself, because I knew that this story was one of the true stories of our times. It was a way of really understanding what happened in my segment of American society at that time, and it had to be told — a story of buccaneers and buckaroos. But Hagan missed all of that. He didn’t get that. He wanted to do all the gossip. So I’m glad that I did it. I had more fun doing it than if Hagan had turned out a good book.

“Hunter gave you a feeling that this would be the craziest, most extreme, most drama-filled night of your life...”

How did the process of writing about your life change the way you viewed it?

JW: It was really reassuring and it made me feel good. I always tend to discount everything, or give too much agency to outside forces, or think that things would have happened anyway. I’m a little modest in that way, which is strange to say. But when you sit down and look at it all, and add it all together, it’s sort of impressive. It all makes sense. And when you do that, you realise that you were the common thread. So the summing up is really impressive and self-fulfilling.

I totally enjoyed doing the writing, which I didn’t think I would. To do this right, to write well, you have to really go back to that place you’re writing about. And only if you get there can you find the right words to bring it back. So you’re really reliving it, and recovering all this memory you might have forgotten. And that’s so refreshing and revitalising — and it’s necessary to the writing process.

Was it ever particularly painful to revisit the past?

JW: It was poignant in lots of places. I cried a few times when I was writing it. Usually at people dying, loss. But it was full of real poignant and moving memories — thinking of people you loved. Just to re-experience a love affair, and to relive moments that were so wonderful and are now gone. It was just emotional in a lot of places. If I was writing about something, I could feel the pain again.

Do you have any regrets?

JW: There are always mistakes you made and you wish you could take back, sure. But not to the extent of constantly regretting things. I don’t have regrets about my life overall. I love it.

Do you think about legacy a lot?

JW: I don’t think about it. I stated my case. That book — that’s my statement of my legacy right there. I feel like it’s fairly stated and put into context and done accurately.

But, really, I don’t worry about it.

Like a Rolling Stone by Jann S. Wenner is out now in paperback, published by Little, Brown and Company.

This interview was taken from Gentleman’s Journal’s Summer 2023 issue. Read more about it here…

Become a Gentleman’s Journal member. Find out more here.

Become a Gentleman’s Journal Member?

Like the Gentleman’s Journal? Why not join the Clubhouse, a special kind of private club where members receive offers and experiences from hand-picked, premium brands. You will also receive invites to exclusive events, the quarterly print magazine delivered directly to your door and your own membership card.