From the first moment Mohamed Fayed settled his Chelsea-boot heels on the pavement of Park Lane, a contract was already out on his name. Posing as a Kuwaiti Sheikh for most of 1964, he had promised the feared leader of Haiti, François ‘Papa Doc’ Duvalier, an oil refinery on the turbulent Caribbean island. Lab tests had revealed that the oil Fayed had ‘discovered’ there wasn’t, as it happened, oil — it was treacle from a sugar cane plantation. Fearing reprisals, Fayed fled the island with the dictator’s cash. Haitian state newspapers declared that Duvalier’s death squads, the Tonton Macoutes, would search the world to avenge Papa Doc’s humiliation.

Aged 35, a conman and a crook with a fabulated backstory, Fayed arrived in London much the same man as when he left it, six decades later, on 30th August 2023.

It was from London, however, that Fayed was able to craft the story of his life: a story he would adapt and distort at will; a story that allowed him to sneak into those rarefied corridors of power – marble boardrooms and royal courts; canapés on manicured summer lawns. Inch by inch, Fayed used the power of this story to carve out greater territory, chipping away at parts of the capital with the studied crudeness of a stonemason breaking rocks. From the decades of chipping and carving, the area you might now designate as ‘Fayed’s London’ emerged.

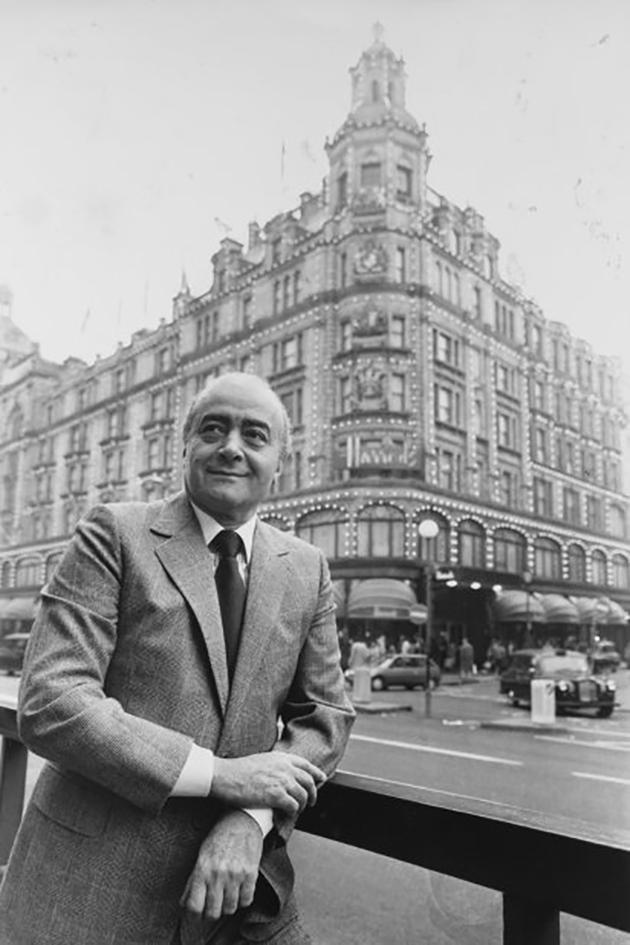

Fayed pictured outside Harrods – the iconic symbol of British luxury that he owned between 1985 and 2010. Image: Getty

It spills out from the man’s first and favourite home on 60 Park Lane, into Knightsbridge and Harrods, towards Pall Mall, Parliament, Fleet Street, a drive past Buckingham Palace, and then all the way over to Fulham on the banks of the Thames. You can chart Fayed’s fortunes along these corners of the capital: the places he bought or bought into, the sites of his greatest celebrations and deepest humiliations.

They tell London’s story too: the tale of ‘Mohamed Al Fayed’ (the ‘Al’ was another invention, conveying blue blood that did not pump through his veins) is the story of a city in flux; a capital looking to rediscover its place in the world. It speaks to the singular nature of London life that Fayed was able to find his billions there; that he could operate with impunity there, often in full view of the gawking TV cameras, as he transformed himself from pretender to plutocrat. To follow Fayed through the changing capital is to watch the iodine in the bloodstream illuminate behind the hospital backlight – stand back and you’ll see where power lies, not just locally but globally.

When he first arrived in the city, Fayed found London a place full of fellow-minded chancers – men with money and means, and an urge to rediscover some sense of greater purpose in the great malaise that was 1965. He rented a ground-floor flat at 60 Park Lane and, for a moment, he was rooted to the ground. Over the course of his life, Fayed would unmoor himself from that first lowly tenement up towards the top floor, to the penthouse with the grandest view of Hyde Park, then to a couple of other flats in the building for his family, and then two or three more for good measure.

60 Park Lane was Fayed’s initial powerbase, the place where he would begin crafting the artifice that most would come to associate with him for the rest of his life: that of the ‘Phoney Pharaoh’, an Egyptian tycoon with the ear of the world’s most powerful men. “He was big on symbolism,” remarks Mark Hollingsworth, an investigative journalist who spent a couple of years in Fayed’s inner circle as part of a failed ghostwriting project. “And he bought in for the address – to be on London’s famous Park Lane, not for the property itself.” Soit stands: there’s nothing remarkable about the building of 60 Park Lane except its proximity to better things nearby.

Image: Getty

Announcing his arrival in the area with a brio that presaged so many rich men in Knightsbridge, Fayed bought himself a white Mercedes-Benz and began making his presence known. His talent was seeking out patronage. His downfall, so far, had been in maintaining it. First, he’d had the good fortune to go into business with a young Adnan Khashoggi, scion of the Saudi king’s personal physician; then, he married into the family, falling in love with Adnan’s sister, Samira. But in 1956, as the first flushes of wealth came into his life, Fayed betrayed Samira through adultery, and found himself cast out of the Khashoggi clan just as they were growing into their status as one of the world’s most powerful and influential families.

With neither a Khashoggi or Duvalier to leech from, Fayed found his footing by using 60 Park Lane as an unofficial consulate between the eager moneymen of the Gulf and the reckless speculators of the West. Fayed’s meetings facilitated the growth of modern Dubai, connected him with Emirati royalty and, crucially, helped him sustain an image of omnipotence as a fixer who could find his way into anyone’s company. “He was desperate to be integrated,” notes Hollingsworth, “desperate to be accepted.” During this time, through the sleaze of the 1970s, he’d meet his next target for patronage, a friend and a foe in equal measure: Roland ‘Tiny ’Rowland, another outsider just like him, trying to buy his own way into the British establishment.

Rowland was a spectre on British life. A childhood Hitlerite born in a military internment camp in Calcutta, his name was the byword for rapacious resource extraction following the fall of the British Empire, with his company Lonrho (London and Rhodesian Mining and Land Company) being publicly castigated by Conservative Prime Minister Edward Heath as “the unacceptable face of capitalism”. To Fayed, he was a kindred spirit. In conversation, Rowland was ‘Tiny’ while Fayed went by ‘Tootsie’. Both found their backing from untapped resources: Fayed from the Gulf, Rowland from Africa – and both wanted to buy a seat at the table with the economic powers that had run the world for cen-turies from this proud, regal city.

"His talent was seeking out patronage. His downfall, so far, had been in maintaining it"

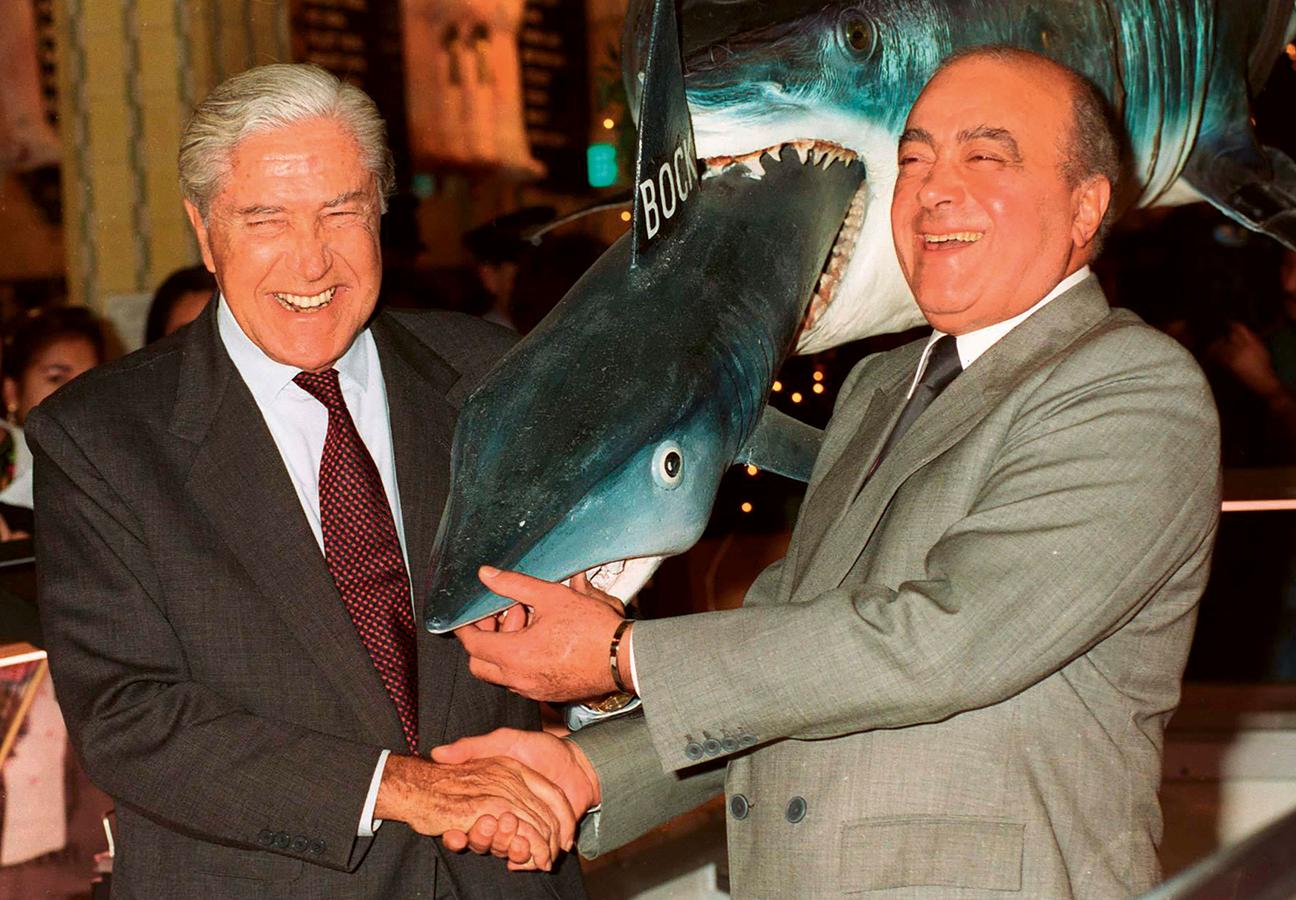

At first, they worked alongside another, hand-in-glove as swaggering rebel tycoons amid the long process of laundering their tarnished reputations. Fayed bought and renovated the Ritz in Paris, while Rowland tried to take over the long-established House of Fraser group, in a move that would bring the legendary Knightsbridge department store, Harrods, into his ownership. Both men recognised the power that Harrods could hold for them – the gifts they would be able to bestow, the shoulders they could rub against. In the fast-money early 1980s, Fayed sensed a chance to snatch the store from under Rowland’s nose. He’d talked his way into holding power of attorney over the wealth of the Sultan of Brunei, something Rowland steadfastly refused to accept as Fayed told him of his intentions. “But, Tootsie,” he reportedly told him, “you don’t have the money.

Fayed didn’t but, incredibly, it didn’t matter – the right people were conned, Thatcher’s trade secretary Norman Tebbit waved Fayed’s bid through the process without investigation, and the Egyptian took ownership of the Queen’s department store on 14th March 1985. “First Suez, Now This,” declared one newspaper. “Nothing Is Sacred.”

Mohamed Fayed and Tiny Rowland reconcile in Harrods Food Hall in 1993, ending an eight-year feud. Image: Getty

Harrods became his new centre of operations, his own royal court, and over time he would come to develop it into the instrument of influence he’d hoped it could be. Ruled like a shadowy, corrupt fiefdom, and further styled in the chintzy and ostentatious tones of its increasingly megalomaniacal owner, Fayed’s Harrods was always a dark and unhappy place, one where the grubby shove of pinched notes into shirt pockets covered a litany of abuses and transgressions. Hollingsworth remembers the internal atmosphere. “The Harrods boardroom was always drab and grey,” he says. “But Fayed’s office was different: ridiculous amounts of gold, drapes, exotic ornaments, real displays of wealth. And he always kept the curtains closed.”

With Harrods purchased, Fayed now had more than another set of deeds in his possession: he had a brand, one which had preexisting formalised links with the royal family, sponsoring events close to their heart like the Royal Windsor Horse Show, held upon the verdant western shires of the capital’s hinterlands. Now able to seek patronage with the family who had controlled the port city of Alexandria he had grown up in as a boy, Fayed threw himself into the mission of seducing the House of Windsor by any means necessary. Maybe, if he charmed them just so, they would extend to him the ultimate hand of friendship: an offer of British citizenship, and a burgundy passport with the latest version of his name inside. He tested this theory doggedly, with a now-idiosyncratic lack of subtlety.

In late 1985, he moved to help finance the restoration of the Villa Windsor, former Parisian pad of the abdicated Nazi king, Edward VIII. Fayed’s restoration was as reputational as it was structural – he rebuilt it to regal standards, maintained the Duke and Duchess’s assets, and kept the flat sparkling as a symbol of British soft power (now with Egyptian assistance) at the heart of the Entente Cordiale. Back in London, Fayed moved elsewhere, targeting Prince Charles by the cufflinks in buying his favourite shirtmaker, Turnbull & Asser, and its flagship store on Jermyn Street in the heart of London’s clubland. “Here was Fayed buying another real trophy asset,” Hollingsworth says, “and one with real social implications.”

Frustrating Fayed throughout all of his travails was the scorned Rowland, who used his Sunday newspaper, The Observer, to pursue perhaps the most single-minded and persistent defamation campaign in the history of the British press. Not to be bested by his fellow grand panjandrum, Fayed bought politicians instead of papers, and, in the process, carved his way into yet another national institution, the Palace o fWestminster, keeping men in both chambers. In the wake of the Harrods sale, Rowland’s Observer never tired of underscoring to Fleet Street that Fayed’s money was not his own, that he’d duped creditors on the strength of his association with the Sultan of Brunei, that he was an outsider who had conned his way inside the tent. All three points were incontrovertible, somewhat obvious facts, bolstered by the further absurdity of Rowland playing star witness to each of them. And Fayed had,so far, gotten away with them all.

What followed is best summarised in three sentences by the tireless campaigning journalist Paul Foot: “Fayed did not want the facts of his background and his takeover of Harrods to come out. He bribed politicians to try to ensure a cover-up. When that failed, and the damning DTI report was finally published, Fayed became angry because his bribes had not worked.”

It was his failure to buy his way out of trouble with the DTI report in 1987 that really engaged Fayed’s sense of grievance – and his lust for vengeance. He cast his net wide for people to target, notes Hollingsworth: “Really, he was interested in cultivating people. If you were useful, he would suddenly invite you to Harrods.”

Once you were in his company, you were a target for his generosity: a clip full of fifties here, a trip to the Ritz or a Harrods hamper, and he’d have you. Tory MPs like Jonathan Aitken, Ian Greer and Neil Hamilton took gifts in exchange for services, parliamentary questions and introductions, or, more simply, silence. As the capricious Egyptian demonstrated in the 1994 scandal that sealed the fate of the outgoing Major government, Fayed was unafraid to cast those same contacts aside once they’d exhausted their utility to him.

As his influence and power swelled to-wards its peak, Fayed fortified himself with a ruthless security apparatus. By 1995, he had developed something of a private army: ex-SAS men equipped with Walther PPKs and machine guns. Supporting them was a regiment of spokesmen, spies, lawyers, strategists, toadies, thugs and pimps, all of whom were happy enough to take the money and turn the other way when confronted with Fayed’s predilections. The first great point of confrontation came with Maureen Orth’s report on Fayed and Harrods for Vanity Fair in September 1995. In the feature, Orth exposes just how far-reaching Fayed’s power extended, and how sinister he could really be in deploying it against his members of staff. Longtime employees were fitted up on vexatious theft charges; shop-floor workers were subject to racist or sexist abuse, or gropes and propositions followed by lavish gifts for silence. Complainants were monitored and stalked by Fayed’s goons, and pursued until silenced.

Failing to resist the habit of a lifetime, Fayed then tried to sue Vanity Fair into silence and, as such, found a new home-from-home in the centre of London: the Royal Courts of Justice, where for two years he fought a libel case against Condé Nast.

"Really, he was interested in cultivating people. If you were useful, he would suddenly invite you to Harrods"

Henry Porter was the magazine’s London editor during this time, and soon found himself in Fayed’s crosshairs – despite never once meeting the man. “He tried to set me up with a criminal charge, through an intermediary, with a videotape that was meant to be Fayed and a secretary in his office,” Porter recalls. “I immediately spotted it as a set-up. I couldn’t possibly buy it, as it would be receiving stolen goods.”

Porter continued investigating Fayed for around two years afterwards, furthering the leads from Orth’s September 1995 feature. “He totally took out those two years, ’95 to ’97... He was an omnipresent experience.” As Porter remembers the strength of the rebuttal Condé Nast had prepared for Fayed, he is certain that the direction of the legal proceedings were only going one way by the summer of 1997. “We managed to find enough evidence where he could not have gone to court [and won]... I was determined to go to court with the case, and that would have happened.”

Back at 60 Park Lane at this moment in time, lying in the bed of the lavish top-floor penthouse, was Dodi Fayed: Mohamed Fayed’s feckless, spoiled son, who lived on the foam skimmed from the Fayed and Khashoggi family trusts, and did very little of note beyond accidentally bankrolling 1981 Oscar winner Chariots of Fire. Next to him was another lost soul of high society – Diana, Princess of Wales, who was enjoying the last love affair of her short life in the court of the House of Fayed.

Fayed furnished his son with everything he could possibly need to enhance his seduction methods – the penthouse with the Hyde Park view, the yacht Diana brought Harry and William along to on their final holiday together, and a romantic stay at the Ritz in Paris, complete with a personal chauffeur. After this courtship, and against everyone’s expectations, the Fayed family would be bound into the British Aristocracy, accepted into the fold at last.

You know how their story ends. Fayed lost his son in the Pont de l'Alma tunnel on the 31st August 1997, and the shock of that grief coloured every last action Fayed would take in the final quarter-century of his life. The spectacle of mourning Diana dominated London that September, swamping the Palace and its environs with flowers, cards and portraits of the People’s Princess. The spectacle for Dodi, however, arrived wherever Mohamed appeared, centring itself in the immediate aftermath at a new area of Fayed’s London, Craven Cottage, home to his latest acquisition, the Third Division team Fulham Football Club.

Fayed’s crudeness, largesse and showmanship found a natural home in professional football. Money went further – it cost less to impress thousands of fans with a few star players than it did to buy the approval of a few hundred aristocrats. From the chairman’s box he would watch and weep for Dodi, then listen to the fans cheering his name and feel soothed. He brought his friend, Michael Jackson, to watch the side as they ascended the English football pyramid, not without making an unprintable homophobic joke about Jackson in the company of his first-team squad, as manager Kevin Keegan recounted to The Guardian years later.

Fayed sponsored events close to the royal family's hearts, such as the Royal Windsor Horse Show. Image: Getty

Over a decade later, he would force a statue of Michael Jackson to remain outside the stadium, even as fans blamed it as the superstitious cause of their bad form. All the same, for delivering their club the greatest successes they have ever known, Fulham fans are possibly the only group in society with consistently warm memories of Mohamed Fayed. Perhaps you can credit Fayed with pioneering what we now call sports-washing.

Cut off from his entry point into the blue-blooded classes through his son, Fayed realised the only real asset he had left was himself, and that he was better off seeking the adulation of the people by decrying the system he’d spent his life trying to wheedle into. From TV studios across Shepherd’s Bush with Ali G, or in the company of fawning celebs like Keith Allen in the risible, fellatory 2004 documentary You’re Fayed!, he rebuilt his image as a cheeky, kooky Arab tycoon with a wallet full of cash and a dirty joke about the Queen or Prince Philip to spare. Hollingsworth is clear on the man behind the image: “He was not a particularly gregarious person. You’ll see him on screen being very smiling and extroverted – he wasn't, he didn’t have friends. He was not social.”

"Fayed's crudeness, largesse and showmanship found a natural home in professional football"

The only pursuit that really animated him in his dotage was, as Hollingsworth says, his claim that Dodi and Diana were killed by MI6, an accusation he made near-constantly from February 1998 onwards without ever providing any further evidence. He continued to broadcast it with such vituperative zeal that Harrods lost its formal partnerships with the Royal family by the turn of the millennium. Undeterred, Fayed paid for documentaries to be made and investigations to be furthered. “He really believed it, he really did,”Hollingsworth tells me.

Henry Porter takes a firmer view. “Fayed was responsible for their death,” he states. “It was his car, his driver who was drunk. His pursuit and manipulation, through Dodi, of Diana. He was responsible, no doubt about it. Nobody else was.”

The borders of Fayed’s London began to recede by the end of the noughties, as he withdrew further from public life and towards his country manors in Surrey and Scotland – away from the capital that made him. He sold Harrods to the Qatari royal family for £1.5bn in 2010, an exchange that would have been utterly remarkable 25 years prior, but was now just another Knightsbridge property deal, an asset trade in a global marketplace. Fulham was sold three years later to the Pakistani-American billionaire Shahid Khan, whose modest stewardship of the club has failed to elevate him to the cult hero status that Fayed enjoyed as Chairman.

But even as Harrods came under the ownership of the Qataris, and Fayed’s retirement was sealed, the last traces of his London still flickered in one corner of the old department store, at a memorial entitled Innocent Victims. Stood as it was, Dodi Fayed and Diana Spencer were depicted as dancing statues, releasing a dove of peace to the sky, standing over the main display. Below were two individual portraits – both taken from times before they knew each other – oval-cut into the marble facade and then intertwined, above a garland of flowers, the last glass Diana everused, and a ring that Fayed alleged was the one his son had planned to propose with, unifying the Fayeds with the Spencers for evermore. It was an exercise in classlessness so extreme as to veer into kitsch, and yet, at the former owner’s insistence, it remained on full display until January 2018: a gaudy eyesore, built on untruths, ignorant of harms, incongruous in the company of good taste – like the career of the man who had it installed.

This feature was taken from our Spring 2024 issue. Read more about it here.

Want more features? Read our interview with Anderson .Paak…

Become a Gentleman’s Journal Member?

Like the Gentleman’s Journal? Why not join the Clubhouse, a special kind of private club where members receive offers and experiences from hand-picked, premium brands. You will also receive invites to exclusive events, the quarterly print magazine delivered directly to your door and your own membership card.