If there’s a crisis in masculinity today, it’s because there’s a crisis in men. Remember that Pixar film Inside Out? That jolly animation where the different emotions and moods were anthropomorphised into colourful, conflicting, but ultimately lovable little orbs of coloured light? If that movie had been set inside a teenage boy it would have been a different film entirely. Everything would be darker, louder, stickier, more frenetic — a sea of many flickering, schizophrenic characters, changing colours at random, sometimes bad-tempered, sometimes over-excited, always at the mercy of impulses and chemicals and images they don’t quite understand. It would be a warzone and a carnival — the brain pinballed this way and that by the conflicting messages of the modern age. Have great abs, but embrace your dad bod. Watch porn, but love your mother. Be strong and courageous, but act tender and kind. Boys will be boys, so don’t be one of those. Be a man, except definitely don’t. Be yourself, but change your ways. Man up. Man down. Man overboard.

Baldoni with his parents at the Golden Globes

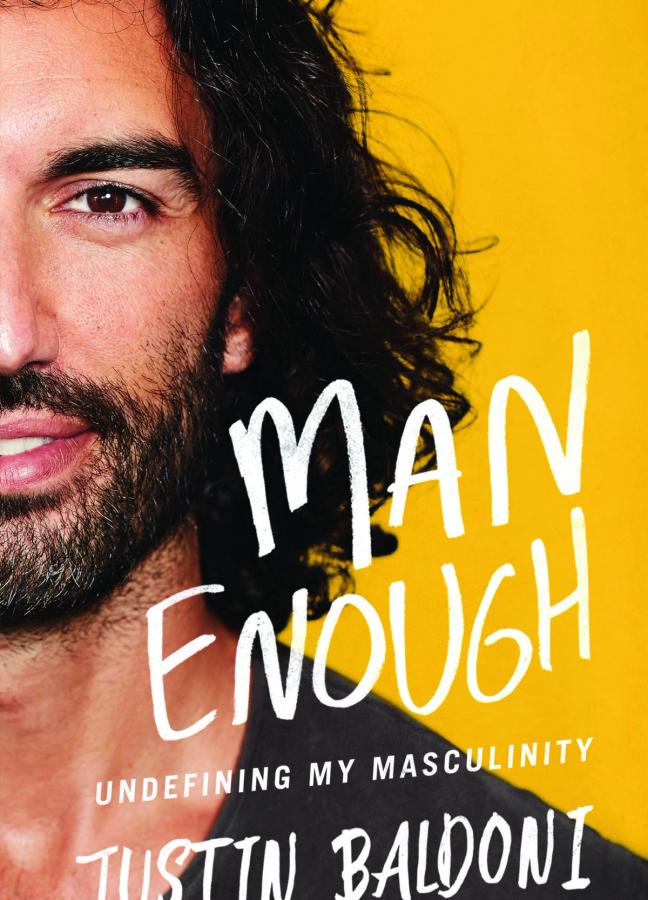

Justin Baldoni, the author of an insightful new book on the topic, knows this culture clash better than most. He certainly seems well placed to answer its trickiest, stickiest questions. A Hollywood actor-director with leading man looks and a quite wonderful, man-bunned head of hair, he would seem, on the outside, to be a prototype of modern male perfection. He is happily married with two children, and lives in a Californian home that appears, in our Zoom call at least, like a sepia-toned film set; the golden-hour backdrop to a rom com happy ending. He has famous friends, excellent teeth, and rich, baritone voice, and on screen he’s often cast as a character of brooding machismo and lusty manliness.

But the problem, as he explained in a famous 2017 Ted Talk, is that Baldoni often felt quite different when the camera stopped rolling. He wasn’t just playing a role for his directors — he’d been playing a role his entire life: for his peers, for his girlfriends, and even for his parents. The Ted Talk, which has racked up 7.3 million views and earned a tearful standing ovation, is titled “Why I’m done trying to be man enough.” And it is the first step on a long, labyrinthine journey into the young male psyche that winds through Hollywood, politics, the boardroom, social media, pornography, and several generations of parenting — and culminates, perhaps, in this compelling new book.

"I've had a lot of bee stings regarding masculinity in my own life, which have culminated in this allergic reaction to bees..."

When we chat, Baldoni speaks as if the world is his Ted Talk, perhaps —with earnest wisdom, but an awareness, too, that he doesn’t have all the answers. He is more an older brother than a hectoring patriarch — a few steps ahead on the journey, but not the finished product. He has clearly thought about the issues a lot, and deeply, and the book is given resonance by its clear personal importance to him. But mostly, you sense, it is a love letter to men as opposed to a scolding diagnosis of their flaws. Here, we discuss the many ‘bee stings’ of modern existence, the psyche of 13 year-old-boys, and why the phrase ‘toxic masculinity’ helps no-one whatsoever.

GJ: Was there a single, penny-drop moment for you when you realised that men in general might be undergoing something of a crisis?

Justin: I don’t think there was a single moment for me. I think it was a culmination of a lot of small moments. In my book I reference ways that I have been unknowingly, subconsciously racist, and hurt people in my life. I describe all of these micro-aggressions as bee stings. And I have had a lot of bee stings regarding masculinity in my own life, which have culminated in this allergic reaction to bees.

Even now, in my late 30s, being a father to two kids, and being married now for eight years, there are so many incidents — even despite my research and having written a book on the subject — where I find myself still being stung and having allergic reactions. It’s the moment when we as men puff up our chest and say something totally ridiculous in front of another person, whether that be a man or a woman, and we don’t know why we said it. It’s the need to feel powerful over somebody else in order to have confidence. It’s me interrupting my wife without recognising or realising I’m doing it. It’s the way I feel insecure or less-than if something that I’m doing in my career doesn’t go as well as I think it should. It’s that weird, paralysing feeling I get when I want to confide in another man but I don’t, because I’m worried they’ll use it against me.

I just began noticing how trapped I felt and how unhappy I was. I just felt like I was trying to be somebody I wasn’t and I didn’t know why. I had the feeling that I didn’t know how to connect with myself — that I was cut off from my own body, a floating head. I realised that I severed myself from my own emotions for so long. It would come out as anger, as rage. It was thanks to the women in my life, who had been lovingly and patiently pointing out my problematic behaviour… My wife has held a mirror to me and my masculinity over our time together.

"I just began noticing how trapped I felt and how unhappy I was. I just felt like I was trying to be somebody I wasn’t..."

GJ: To what extent are the current issues around masculinity personal, and to what extent are they bigger than that — political and societal for example?

Justin: So much of this is learned. Masculinity shows up, by the way, in both progressive and conservative areas of politics. Which is why I don’t use the phrase ‘toxic masculinity’. It’s a buzzword. It’s political. It’s been weaponized. It cuts you off from even being able to enter the conversation, because it’s been so misused over time. That’s not to say there aren’t parts of masculinity which, left unchecked, could become toxic. But too much medicine can become like poison.

I just think it’s important that we look at masculinity as a whole, and realise that masculinity in itself isn’t the problem. It all stems from a misuse of power. That’s one of the byproducts of living in a patriarchal culture. We’re told we must achieve power, and that the way to achieve power is by dominance. So you have a lot of leaders who are leading by brute force and dominance, and creating very unhealthy organisations where people don’t feel safe. That exists in politics, in companies, everywhere. What you find, in general, is that women-led organisations don’t have those same cultures. Are women better leaders? I wouldn’t necessarily say so. But have women been taught that their empathy and compassion and sensitivity are cultureall acceptable traits for them to have? Yes.

On the other hand, we’ve had boys who have been told they’re not allowed to have those qualities. Because if you do? You’re a woman. You’re a girl. And that’s an insult to men — which tells us that women are less-than. When we say these things, we’re being taught as young boys to view women as less-than. By the time we reach business level, we’ve killed off that part of ourselves, and engaged in a psychic act of self-mutilation.

What’s your advice for a 13 year old boy right now? It’s hard to be a teenage boy at any point, but it must be twice as hard in 2021, especially growing up hearing all the time that masculinity itself is toxic…

It’s really unfortunate that there isn’t space right now in the cultural dialogue to identify the root problem. The problem isn’t these 13 year old boys. Their brains are just forming. They’re growing up at a time when so many messages are being shot at them. They’re being told they have to be a certain way to be accepted as men. They’re being introduced to pornography, and more than likely violent sex. They’re being told they have to be big enough and strong enough and powerful enough to get into the boys club. They’re being told they have to fight to gain dominance over each other. They’re learning these things from fathers and other boys.

Nobody changes their behaviour, nobody heals, when they’re attacked. We have to create space for these young boys, especially at these formative spaces, to not hate themselves. We have to create space for these young boys to feel the pain they are feeling, and maybe that they’re inflicting on others. I believe there is an entirely different pandemic with young boys going on right now. And these young boys need to be brought into the conversation, and loved. We need to teach these boys what it looks like to be full human beings. We’re teaching boys to be like robots. We can’t be shaming these boys. We have to invite them in.

Man Enough: Undefining My Masculinity by Justin Baldoni is published by HarperOne and out now

Become a Gentleman’s Journal Member?

Like the Gentleman’s Journal? Why not join the Clubhouse, a special kind of private club where members receive offers and experiences from hand-picked, premium brands. You will also receive invites to exclusive events, the quarterly print magazine delivered directly to your door and your own membership card.