In the days before my interview slot with Louis Theroux — who was on a promotional run-around for his new documentary about Joe Exotic, that Tiger King chap — I asked a few people what they would ask Louis Theroux if they had an interview slot with Louis Theroux. Every single one of them, almost straight out the gate, said: “oh, you should ask Louis Theroux what he would ask Louis Theroux if he was interviewing Louis Theroux.” Every single one of them. Even the intelligent ones, which meant it was definitely a stupid question. In any case, I already knew the answer (and I’m told that’s the number one rule of journalism: don’t ask questions you already know the answer to), because Jon Ronson had sort of already asked that question. He’d asked it during a special edition of Louis’ very successful new-ish lockdown podcast, Grounded, in which Louis’ former interview guests turned the tables, briefly, on him. So instead, I asked Louis what he thought about Jon Ronson asking him that question, as that seemed a little less obvious. Yes: an interviewer asking an interviewer what he thought of another interviewer asking him what he would ask himself in an interview if he was interviewing himself. You can see why I didn’t sleep much the night before. If this is all getting a little too meta for you — a little too look at me deliberately showing you the seams — then perhaps that’s the point. In fact, it definitely is.

Louis Theroux is the seam-shower-in-chief. He did that before it was cool (and long before Masterclass did all that nonsense with the tech guys adjusting the lapel mic of the guest, and the guest saying things like ‘are we rolling?’ when they know they’re rolling, just to show how cleverly faux-authentic it all is. Are the lapel-mic adjusters actors, too? If we zoomed out again, would we see another lapel-mic adjuster adjusting the lapel-mic adjuster’s lapel mic? Are the edges of the set really the edges of the set, or just another set, of which, presumably, there are also edges? How deep does this rabbit hole go?) On Louis’ podcast, he always includes the tech difficulties and the fumbling with USB mics. In his documentaries, he comments constantly on the process itself: he includes the false leads, the awkward greetings, the production kerfuffles. He shows how the fringes can be more revealing than the centre.

“It’s all about trying to blur the edges between performance and reality,” Louis begins, once our interview is underway, and once I ask him about these kinds of tricks. “Which is kind of what I’ve been trying to do with documentaries since I started, back in 1994. I think a lot of people are doing a similar sort of thing: thinking about how you bring a greater honesty to television-making and podcast-making. Going back years, when I used to watch TV as a child, I used to find it very exciting when you saw things that you thought you weren’t supposed to see. If on Blue Peter the elephant ran amok and you suddenly saw all the cameras and the edge of the studio and you thought wow, this is incredible…”

“I can’t lay claim, in any way, to pioneering or innovating any of that. It was just one of the ingredients I added and put my own accent on. You just have to be wary of it becoming a cliche or overly self involved and tail-chasing. There’s a fine line between intriguingly quirky and tedious and self-indulgent. You do need some meat in the meta-sandwich.”

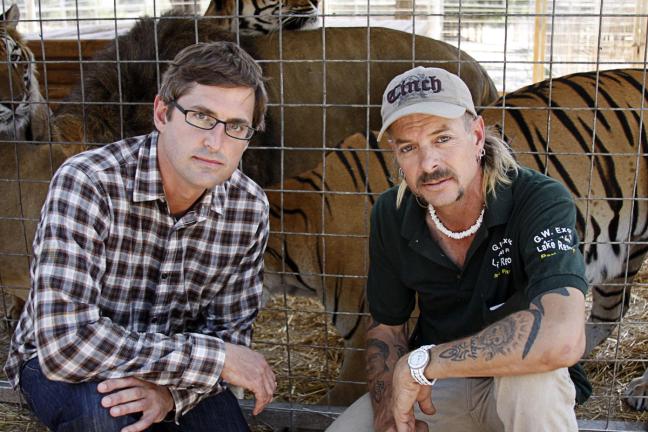

Caged animals: Louis Theroux and Joe Exotic while recording America’s Most Dangerous Pets in 2011

Noted. So here’s the meat; the notional hook for our conversation. (Though it soon turns out to be a sandwich within a sandwich. Wheels within wheels. Cages within cages.) In 2011, Louis shot a documentary called America’s Most Dangerous Pets in which he interviewed Joe Maldonado-Passage, better known as Joe Exotic, at his wild animal park in Oklahoma. Very quickly, Louis sensed that Joe Exotic was different to the other pet owners in the film. “I thought: this guy’s extraordinary — he’s in a three way relationship with two guys; they live in Rural Oklahoma with 250 tigers; he’s got an obsession with Carole Baskin; there are guns everywhere…” The team thought about making a two-part special on Joe alone, but it fell through for various reasons. Nonetheless, they kept acres of footage from their encounter.

Then, in March 2020, as the coronavirus strapped us all to our sofas, everyone found themselves watching a Netflix documentary called Tiger King: Murder, Mayhem and Madness, and they began writing about it in think-pieces and on Twitter. It was the first great shared moment of the pandemic; the kind of event television that is usually reserved for royal weddings or royal car crashes or royal car crash interviews. So, a year after the Netflix doc and ten years after his own, Louis has revisited his old footage from 2011, and updated it to include the latter events of Joe’s story (largely his imprisonment, as you may remember, for 22 years for conspiracy to murder his conservationist rival, Carole Baskin). And he also uses it to make a comment, in some way, on the media furore, and potent cult of personality, that surrounded the Netflix version of events.

"There’s a fine line between intriguingly quirky and self-indulgent. You do need some meat in the meta-sandwich...”

So, what did we miss the first time round? “The part of Joe that’s maybe misunderstood is his vulnerability,” Louis says. “But also the sense that his fragile qualities gave him a kind of power. If you were in his orbit it was hard not to be charmed by him; but at the same time that meant supporting him, and being aware he was thin skinned, and tip-toeing around him. I was conscious that he wasn’t robust in the way that many big personalities are.”

“By the end of the eight or nine days I’d spent with him, I’d run out of road,” he says. Louis remembers trying to get one last, punchy encounter with Joe Exotic to wrap things up neatly. In the footage, the pair end up clashing, and Joe rips off his microphone.

“But what was striking, watching the footage back, wasn’t that he was upset,” Louis says. “It was that I asked him if I could have a hug. It’s not every day I interview someone and then at the end I need a hug from them to make sure they’re okay. It says something about how he was able to solicit those feelings of protectiveness from those around him. But I needed the hug. He didn’t even want the hug.”

The story also takes on a new post-Trumpian flavour, Louis points out, that perhaps wasn’t immediately obvious last year. “I’d like to acknowledge the slightly eerie parallels that exist with the Trump vs Hilary Clinton duality,” Louis says. “In Joe, you have a shameless but charismatic and flamboyant man with weird hair who has this unlikely hold over vast numbers of people; and [in Carole Baskin] this more responsible, more correct, more thoughtful person who is for some reason viewed as censorious and pious and irritating — unfairly, in some respects.”

At this stage, I start to worry that we’ve gone a bit too deep on all the Joe Exotic talk, even for a conversation nominally pegged to talking about Joe Exotic. At one point, Louis says: “I’m sorry, Joe, I’m sort of hijacking this, is that okay?”, and I slightly feebly joke that “it makes my job a lot easier,” and we chirp merrily on. What would Louis Theroux do at this point in an interview with Louis Theroux? On Grounded, he displays a subtly different style of interviewing which prevents this sort of friendly hijacking. In the podcast arena, Louis can no longer be the gently probing wall flower of his documentary persona — the gawky wisteria, the subtle needler — waiting for the mask to slip. He doesn’t have eight days. He has two hours, with a hard-out at 5pm. He has to drive the agenda; pull at the mask himself. It’s not Jeremy Paxman. But it’s not Oprah, either. (Is it Emily Maitlis, then? I’m lost in this analogy myself.)

“I’m sorry, Joe, I’m sort of hijacking this, is that okay?”

“I’m a younger brother, and sitting in the back of the car and being driven around, and being the passenger in the family, is a very comfortable and familiar role for me,” Louis says. “In many ways, I’m a slightly Beta person. I’m not an alpha. If there’s a fire, I’m not the person in the room who’s going to be saying ‘everyone stay calm, make for the exit, move away from the smoke’. I’m not that person. I might be cracking a joke. Or complaining. Or just meekly following wherever everyone else is going.

“In the journalistic realm that can be an asset, because you’re not the largest person in the room, and you’re just listening and noticing. In a podcast, you have to step up and drive it, and in certain respects I find that much harder; much less relaxing.” Instead, Louis goes straight for the elephant in the room.

“I am a believer in attempting to stake out the parameters of what you’re interested in. What is the moral question that we are nibbling away at? Why tip-toe around that? Just get it out there, and see where it takes you. When I get impatient as a listener, it’s when it feels like two mates having a natter. I do like the sense that it is a high wire act, or a clash, or some sense of pushback. Cosiness to my mind is so boring.” Of his documentaries, Louis admits that the most revealing moments often come from the clashes, the apple-cart-upsets. “The best part of the interview is often when people end the interview. Any time anyone rips off their mic, or puts their hand over the lens, you’re thinking: this is going in.”

But Louis only spars within the sanctity of the ring, if you’ll permit this metaphor. He is not a street brawler by any stretch. There’s too much of that going on already — on Twitter, on Good Morning Britain, in the Commons. “There’s a reason why, for a living, I talk to other people,” Louis explains. “I’m a hesitant and irresolute and self-questioning person. I’m not without opinions, but those that I do have I tend to question. You listen to people on the radio and talk shows, and they specialise in certainty and outrage, and those are the parts of my personality I have attempted to weed out.”

"It gives me very little to say on Twitter, other than I’ve had a nice cheese sandwich."

“There’s a quote about Henry James that says something like ‘his mind was so pure there was no idea that could violate it.’ I try not to have too many views on anything. In the end, it gives me very little to say on Twitter, other than I’ve had a nice cheese sandwich. I don’t really want to be another voice expressing an opinion. I’m not sure what good that does, a lot of the time.”

But opinions are everywhere right now, and everyone else’s is wrong. (A cheese sandwich? What about the lactose-intolerant community!) “We now have this x-ray into the soul of the world, which is social media,” Louis says. “We can see beneath the surface of the dominant narratives. It used to be that we could only hear crazy people on radio phone-ins, or writing into newspapers. That has now been multiplied ten million-fold and become the dominant national discourse. In many respects not for the better.

“But it’s not without its positive dimensions. There’s definitely a sort of intriguing cacophonous political and cultural free-for-all that is in some ways exciting, and in certain ways has killed sacred cows. But there’s also a part of it that is massively destabilizing.”

Louis holding a picture of a young Joe Exotic, at what remains of his home in Oklahoma. Photographer: Jack Rampling

I ask Louis about some of the more adversarial encounters of his career. Jimmy Saville is the most interesting and obvious and tricky example, so I don’t go for that. But there was a BBC documentary out just the week before about Max Clifford, the tabloid-whisperer and serial rapist who Louis interviewed on the When Louis Met… series in 2002, long before his convictions. What does he remember from that encounter?

“It’s like paying the Danegeld — like when they used to pay off the Vikings back in Anglo Saxon times. You pay Max Clifford, and you’re safe. But the minute you’re off his books, he’s presumably going to spread your secrets to the world. He seemed to have two main techniques — both for embarrassing you and for building you up. And they would usually be the same thing. He would find a dancer from [the strip club] Spearmint Rhino, and say: I’ll get you in the papers coming out of the premiere for the Smurfs movie, and you’ll have the cover of The Daily Sport or The Star. But then his way of embarrassing you is to get you linked to a woman, as well. When he wanted to embarrass me he coaxed me down to Spearmint Rhino, and got pictures taken of me with one or two of the dancers there. His bag of tricks was really just one trick.”

I ask him whether he thinks Max Clifford could thrive today. “I think probably not. The decline of newspapers, the ascendancy of social media and virality, has put paid to that. Presumably some version of those people exists. But I don’t quite know who or what it is. Or maybe it doesn’t, and maybe that’s the point.” With social media nowadays, he says, “perhaps the good part is that there’s a sort of multiplicity of voices, so that actually you can get your version out. Certainly, there’s a lot of people who can challenge and fight back.” (If Twitter kills off any proto Max Cliffords, it might not be such a bad thing after all.)

"When he wanted to embarrass me he coaxed me down to Spearmint Rhino, and got pictures taken of me with one or two of the dancers there."

In Louis’ 2019 memoir, Gotta Get Theroux This, he writes about how odd it felt to suddenly be the subject of tabloid attention, after Clifford deploys his trusty trick. He was suddenly, briefly in the centre of things, while his interviewee was at the fringes, seemingly pulling the strings. To be ‘the story’ for Louis seems disquieting and conflicting; a messy meta sandwich which the whole memoir — a book, remember, that puts him right at the centre of things — nimbly juggles. (Even the title is plucked from that odd Louis Theroux-niverse — the punny, knowing fandom that spans all the way from humorous mugs with his face on them, and ends with people getting his image tattooed on their flesh. Lots of them.)

In the afterword to the book, Louis writes how he had once dreamed of being a kind of recluse savant: “the Banksy of BBC2 documentaries”. But, he later realises, “in the spirit of an aristocrat fallen on hard times,” he should let the public “into my metaphorical stately home, guide them around, show them the old curiosities, the back rooms.” In the end, he concludes that “having charged people for a ticket to see the house, the idea of roping off the more interesting parts of the property seemed unfair.” The only thing he regrets, in fact, is that he didn’t make it “even more personal and painful.” The elephant in the stately home.

Which brings us back to that question at the start. The one that everyone else asked me to ask, and the one which I swore I would never ask, but which I ended up asking anyway, only worse. What would Louis Theroux ask Louis Theroux?

“That’s a bit like asking the manager of a bank how he would rob his own bank. It’s kind of cheating.” he says. “‘Where are your weaknesses? What is the part of you that is most ashamed and disgusting and ugly?’ But on the other hand, fair question.” (I take it all back.)

“In different ways, I tend to see my fascination with the dark side or with angst or with the most troubling parts of human experience as symptomatic of a kind of projection; an attempt to deal with my own darkness — but by proxy.” And what is that darkness, do you think? would have been a pretty solid follow up here. This, perhaps, is the central question that Louis would have pounced upon had he been a guest on his own podcast. But I didn’t go for it. Didn’t even see it. And anyway, there was a hard out at 5pm. Interviewing Louis Theroux is a tricky thing to do if you’re not Louis Theroux. It’s very reassuring that he is.

Louis Theroux: Shooting Joe Exotic is now available on BBC iPlayer

Read next: At home with Marco Pierre White

Become a Gentleman’s Journal Member?

Like the Gentleman’s Journal? Why not join the Clubhouse, a special kind of private club where members receive offers and experiences from hand-picked, premium brands. You will also receive invites to exclusive events, the quarterly print magazine delivered directly to your door and your own membership card.