When Narcos season two came to an end in September, millions of the show’s disciples began to miss it like a 90s It Girl misses her septum. But an announcement last week means they needn’t worry themselves with harder stuff: The series has been renewed, blessedly, for a third and fourth season. The newsflash flew in the face of earlier reports that the white river had run dry, and conjured up a singular question from the Netflix hit’s feverish fans: how could the show go on without Pablo Escobar?

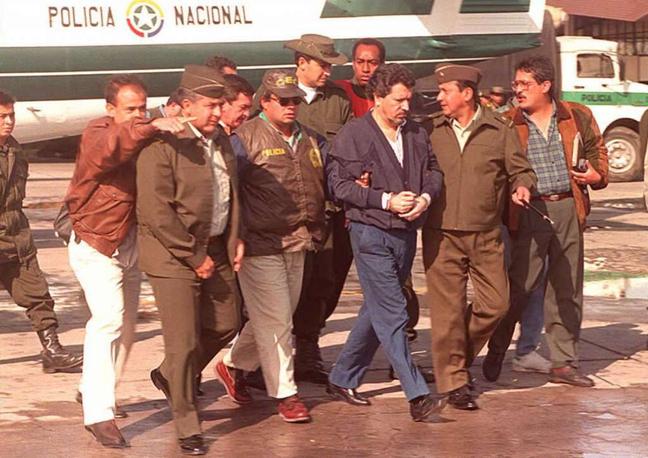

It’s a good question. Those who hoovered up Narcos a season at a time will know that, at the end of the second season, The King of Cocaine was fatally gunned down by Colombian National Police. They’ll also have had a sniff of the infamous Cali Cartel, the gang who – fronted by the Orejuela brothers – made a cameo in season two as the bosom mates of Los Pepes.

And just as the death of Pablo is pegged precisely to historical fact (the drug lord was tracked to a middle-class barrio in Medellin in December 1993, and shot dead by a special task force as he attempted to flee, shoeless, across the city’s rooftops) so too is this next chapter in Colombia’s powdered history scarily accurate.

Because the Cali Cartel, who take centre stage in the upcoming season, were very real indeed. And they make Pablo Escobar look like a particularly elderly Santa Claus, only with less snow and more ethnic cleansing.

So, as we consume the tantalisingly brief season three trailer for the 76th time tonight, allow us to introduce you to the Cali Cartel: The Most Powerful Crime Syndicate in History. Here are five things you should probably know.

After they cannibalized their South American competitors, the Cali Cartel found themselves with more than the lion’s share of the world’s cocaine in their back pocket. It’s believed that the Cartel were directly responsible for the popularity of the drug in Europe, where they introduced it to world capitals and controlled almost 100% of the flow. Needless to say, by the mid-nineties, the Cali Cartel had a net worth to rival that of other colonising multinationals such as McDonald’s and Nike.

In the early 1970s, the United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) announced that it was not particularly interested in pursuing cocaine trafficking, and would be turning its attention to a much more destructive force, heroin. ‘Cocaine is not physically addictive’ they announced ‘and does not usually result in serious consequences, such as crime, hospital emergency room admissions or both.’

Sensing an opportunity, the Cali Cartel began targeting American cities by the dozen. Within weeks, the Cartel had sent Helmer ‘Pacho’ Herrera to New York city to establish a formal distribution centre, from which he controlled numerous newly formed ‘cells’. The cells appeared to operate independently – thus foxing the DEA – yet each one reported back to a ‘celeno’ or cell manager, who then reported to Jorge Alberto Rodriguez, who in turn reported back to the overlords at the Cali Cartel in Colombia.

The structure was soon formalised into something called the 400 Cartel, which quickly went onto to oversee all shipments and distributions of narcotics across the United States. It’s this unique structure that set the Cali Cartel apart from Escobar’s Medellín Cartel. And it all came about thanks to the U.S government.

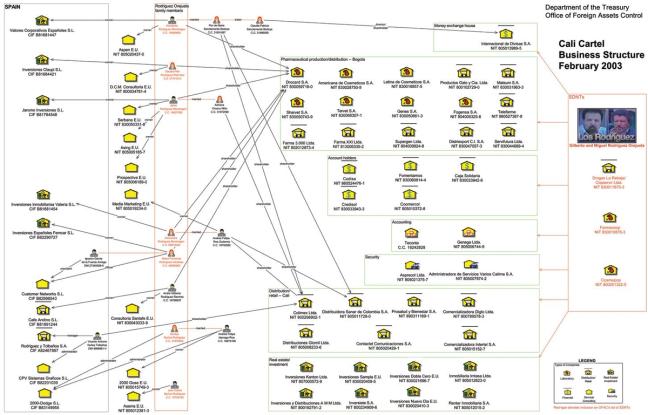

To hide their exponentially growing wealth from the eyes of the law, the Cali Cartel began to invest heavily in a complex web of legitimate business ventures and phoney front companies.

With a ridiculous influx of paper money, the organization needed a way to launder their funds and make them appear legitimate. They did this at first by installing head honcho Gilberto Rodriguez Orejuela as the Chairman of the Board at the Banco de Trabajadores. This allowed the cartel members to deposit cash into bank accounts with no questions asked. It also allowed many members in the high command to open vast overdraft accounts and take out huge loans without any need of repayment.

Soon, Gilberto Orejuela had set up the First InterAmericas Bank, a multinational investment operation based in Panama. This then became the hub for a whole host of international money laundering schemes that would go on to clean the vast majority of the cartel’s blood soaked money.

In his pivotal book unmasking the gang, End of Millennium, the writer Manuel Castells describes how the Cali Cartel set about on an evangelical mission to eradicate thousands of what they saw as ‘desechables’, or ‘disposables’. Those targeted during the bloody purge included prostitutes, street children, petty thieves, homosexuals and the homeless.

With the support of many Medellin locals, the cartel soon formed multiple gangs dubbed ‘grupos de limpieza social’ or ‘social cleansing groups’. When members of these murderous cells struck down a victim, they would leave a sign on their mutilated body daubed with a chilling maxim: ‘Cali limpia, Cali linda’ – Clean Cali, beautiful Cali. The bodies of the victims were then discarded in the central Cauca River, which soon rightfully earned the nickname The River of Death. At one point, the number of bodies in its waters became so great that the municipality of Marsella in Risaralda became bankrupted simply by the cost of recovering them.

What most surprised the DEA and Colombian police when they began to peel back the rotten layers of the cartel’s onion was the level of sophistication in their counter-intelligence technology. After a daring raid of the Cali Cartel offices in 1995, the DEA discovered that the organisation had been monitoring all phone calls made in and out of Bogotá and the town of Cali, including those made from the U.S. Embassy and the Ministry of Defense.

The hacking software was controlled through a specially modified laptop, which was acquired through Israeli intelligence services. The computer allowed high commander José Santacruz-Londoño to listen in on almost any phone call that was made in the area, and also to scan his own phone lines for wiretaps. The encryption techniques used in the process were so sophisticated that it took the U.S government many years to crack them. If that wasn’t enough, comms master Londoño also hired a stooge to work within the phone company itself, allowing him carte blanche among the country’s phone grid.

The Cali Cartel’s bribery gravy train also extended to some 5,000 taxi drivers. These employees were the cartel’s eyes on the ground, and allowed the group an eerily accurate pin on every prominent rival, politician or DEA member who arrived in the city, as well as where they were staying. In fact, the cartel’s monitoring power was so great that, In one attempted bust in Miami in 1991, the DEA was monitoring the Cartel, only to discover that they themselves were being monitored by the Cali surveillance team at that exact moment. With tricks like this in their bag, it’s no wonder that the cartel earned themselves the nickname ‘The KGB of Cocaine.’ It’s also no wonder that Narcos fans the world over now look – with an addict’s impatience – to see how the Cali Cartel’s starring role will play out. The blow must go on.

Become a Gentleman’s Journal Member?

Like the Gentleman’s Journal? Why not join the Clubhouse, a special kind of private club where members receive offers and experiences from hand-picked, premium brands. You will also receive invites to exclusive events, the quarterly print magazine delivered directly to your door and your own membership card.