Plating up Tom Straker’s turbo(t)-charged career

“I put my entire past life on hold and went for the future...”

An unexpected lockdown at a client’s house in New York saw Tom Straker create his first online cooking video. The attention that followed helped catapult him to the top of the London restaurant scene. Just don’t call him an ‘influencer’…

The trick to a decent quenelle, Tom Straker says, is a hot spoon and some soft butter. Then it’s all about a gentle gliding motion, a nifty flick of the wrist, the right sort of haircut — and ‘boom’, as Tom might say: 1.2 million Instagram followers. Or 1.3. Or 1.4, perhaps. Or 2.5, to hedge my bets. Tom Straker’s success moves too fast for fact checkers or sub editors. Any number expires on exposure to air. Its exponential growth has been spurred by the algorithmic pleasingness of those orb-like, glistening ovals of soft, soft butter (burnt butter, chicken skin butter, berry butter, tequila butter, bloody mary butter, parmesan, miso butter — so much butter, so many flavours and shark-jumping innovations, so much churning and swooping and quenelling, that one began to wonder whether everything was quite all right, whether Big Dairy weren’t calling in a mafia debt of some sort).

But it has also, somewhat uniquely, been buoyed by the sense that Tom is not like the other TikTok chefs — the ‘I’m just obsessed with these new tahini carrots’ horde and their very shiny foreheads. He toiled at The Dorchester for three years, working from the bottom of the kitchen up, and shepherded 50+ chefs across the Casa Cruz empire too. His no-nonsense voiceovers could be beamed directly from a sweltering service pass, you felt: “I’m only going to say this once, so you better listen up” (or just play the video twice, I suppose, which to be honest is great for the numbers). And his old Instagram tagline, ‘Food you actually want to eat’ felt true and refreshing and approachable.

I discovered Tom’s account in late 2020, during the depths of Lockdown II: The Park Bench Asahi Years. Back then, he was a shining light for those of us with Small Plate Withdrawal Syndrome, and I made a roast chicken and salsa verde perhaps 14 times, with cabin-fever zeal (the trick is to use fine-grain sea salt, not this fancy Maldon nonsense, to get a really crispy skin. And always remove the wishbone – I don’t know why, but always do).

By then, Straker had found his groove. His very first videos were, he says, pretty shoddy affairs — wrong aspect ratio, too long, bad voiceover, shonky editing. These were made when he was locked down, in mid-2020, as private chef for a family in New York, and found himself with too much time on his hands. Then the clips got a bit better, then much better, then everyone you knew in West London was starting their sentences with Tom’s signature “right then”, then he did a quenelle or two of butter – and the rest, as they say, is history.

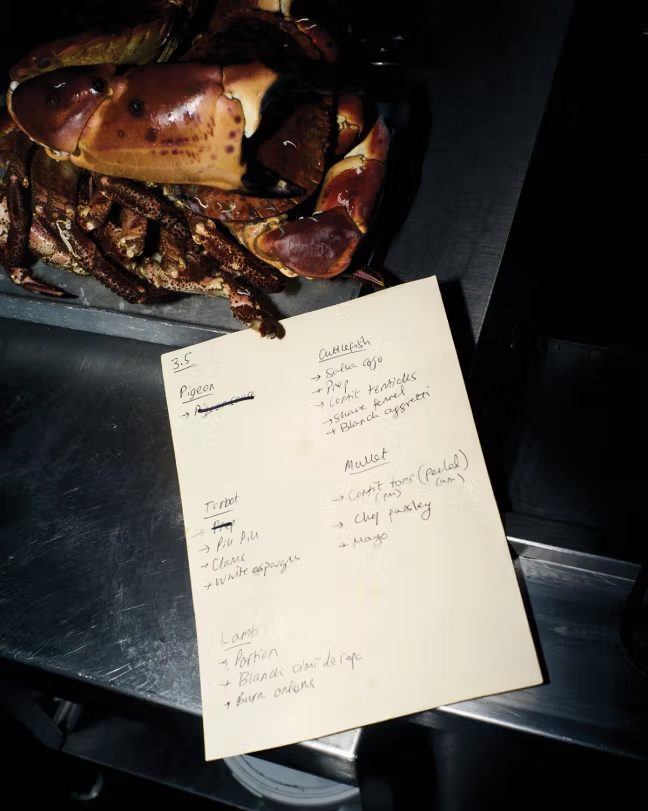

Since then, Tom has opened his own restaurant — Straker’s, on Notting Hill’s Golborne Road — which was sort of the plan all along, anyway. But now, if Giles Coren’s glowing review is to be believed, his social success means diners make pilgrimages to the restaurant from all over the world, while the rest of us struggle to get a table. This is where we meet for interview in late April and to take some portraits of Tom. At one point, during the fizzing, excitable preparation for a Wednesday lunch service, the chef holds a giant fresh turbot to his head while scampering team members look on, and another Tom, the photographer, leans in.

“I don’t usually like all this attention,” the chef admits with a rakish smile.

“Says the man with 1.2 million followers on Instagram,” his maître d’ shoots back.

Somewhere between those two truths lies the unique success of Tom Straker.

Sometimes, the algorithm gets it right.

JB: We’re sitting in Straker’s, the restaurant that bears your name. Was it important to have that above the door?

TS: Originally, I was looking at a different name — I was after something ‘cool’. The naming process was actually quite difficult. At first, I didn’t want to have my name above the door because I wanted a brand that could travel and grow and scale, and not be attached to me necessarily. But Straker’s worked because of the growth I’d had on social channels. It made sense from a marketing perspective. It wasn’t that I said “I need to have my name above the door”, like a complete narcissist.

JB: Do you like getting recognised?

TS: I don’t really think about that stuff. Ultimately, I make cooking videos in a studio in Park Royal. It’s hardly glitz and glamour. But I do feel it in the restaurant, for sure, though I don’t make it too much about ‘everyone’s here to see me’. Essentially, everyone is here to eat food, have a good time, soak up the vibe — we make an experience. But on the flipside, and on the business side, it makes sense to have a platform to launch off. And so being recognised is not a bad thing. Though sometimes if it’s 5am in Soho…

JB: How did that social following get going in the first place?

TS: At the start of lockdown, I was working privately for this billionaire. They said, “do you want to come and watch lockdown blow over in St Barts for two weeks?” And I said “perfect!” But we only made it as far as New York. I was cooking for a family of five, and it really didn’t take me all day to do that. It would take me four or five hours each morning to do breakfast, lunch and dinner. I completed Red Tube in two weeks. And then I thought: shit, what will I do with my afternoons? So I started making some videos…

JB: What were the first videos like?

TS: They were crap. I filmed them all myself, and they were long form, and I didn’t know what I was doing. The whole aspect ratio of the videos was wrong. I was editing them all myself and I was crap at editing, obviously. I’d built up a steady following, and a friend of mine was sharing them on his platform. And then when I came back after three and a half months, I had 15,000 followers. I was cooking every day in my kitchen, and my wife was like “you need to get out”. It was a lot. So we found a studio in Park Royal and built a kitchen, and now we have a production company arm there, where we do longer form video.

But it grew naturally. I never set out to become an ‘Instagram chef ’. All that terminology makes me recoil. But it’s difficult because, on the one hand, I’m really grateful for it, but on the other hand, when we opened the restaurant, everyone said things like “TikTok sensation!” and “Instagram celebrity chef!” Because I’m a chef. I love being in the kitchen. I love the energy there. Everyone comes in fired up, and there’s a mad panic getting ready for lunch, and then service is like Swan Lake, and then there’s a mad panic getting ready for dinner, and then it’s Swan Lake for dinner. But the videos actually exhaust me. It’s hard being this fun on camera.

JB: What’s your first food memory?

TS: I remember I caught my first fish with my dad, and we were floating down a lake, and me and my twin sister had a fishing rod out each side with a fly on the end. I was four years old. We both caught a fish, and we took it home. My dad can’t cook for shit. But he was in the army, so he can make a good fire. He burnt some sausages and cooked the trout — and we had surf and turf. There’s a picture of me holding the trout and the sausage, and it does embody what I like about food — the hunter-gatherer side of things.

A lot of chefs have never been to a farm. But being in touch with where food comes from is important, and I was lucky to be around that. I grew up in Herefordshire and was around farming day to day. My parents kept a few sheep, some pigs and chicken. So it was all lovely growing up. Mum was a great gardener and owned a pub, so I was in tune with all things food.

JB: What were you like as a kid?

TS: I didn’t know what I wanted to be when I left school, because I fucked around a bit. I was naturally reasonably intelligent, but I preferred sport and being outside and causing trouble and chasing women and smoking cigarettes. So I thought I’d go into the army. I failed to get into Sandhurst because they said I was too immature. Looking back, I think, fair enough.

There’s a military aspect to a kitchen — there’s a hierarchy, and a need to be disciplined. But you can create within a certain border — whereas in the army, there’s not much room for creativity. So cooking appealed to me. I did a bad admin job for two weeks, and I knew that desk life ain’t for me.

I found a cooking course in Ireland, and my parents said it was the last thing they’d pay for me to do. It was €12,000, 15 years ago. A three-month course called Ballymaloe. It was a great experience. And when I got back, I went to a festival in Berlin and sitting up late one night, I said to my sister, I’m gonna be a chef. I moved to London as soon as I got back and went to work in The Dorchester.

JB: How did you get that job?

TS: My dad had been for lunch, and an executive chef at The Dorchester had been there, and he’d said “send him in for an interview”. My mum said I had to wear a suit. I didn’t have a suit, so she said, “don’t worry, you can wear your dead uncle’s suit”. I got in this ridiculous, ill-fitting, very large three-piece suit, and I walked in through the front door at The Dorchester. Most chefs turn up to these things in a pair of ripped jeans and some Vans — and here I was in a tweed suit. But I got the job, and did two weeks work experience there. After my first shift in the kitchen, I had prepped 400 heads of broccoli. And I was sitting there at a bus stop, it was pissing it down with rain, and I was waiting half an hour for my bus to Battersea. And I just thought: fuck, I should have worked harder at school. It was that sort of realisation. But they offered me a job after two weeks, and that was the moment I thought I’m going to go for this and do it properly. So two weeks turned into three years.

JB: What was life like in a professional kitchen at that time?

TS: I hit the job when it was transitioning from being a real hard-line ‘my way or the highway’ type place to something else. Everyone cries now and goes to HR. You can’t say boo to a goose. But no — chefs are passionate and highly strung. And if you don’t cut asparagus on the angle, I’m going to come down on you like a ton of bricks.

I had some management coaching because I ended up in a job where I was looking after 50 chefs, and I was 27. A consultant came in and said, you’ve got to get rid of Tom. And Juan Santa Cruz, the owner of Casa Cruz, said: “I really like Tom, his food’s amazing, so just sort the problem”. And so I had an hour a week of management coaching. One of the more interesting things he told me is that you’ve got to be empathetic. If you’re in service, and something goes wrong, and you scream at this person who isn’t getting paid very well, and they’re sat on the bus home because they’ve missed their last tube, and they think, “why the fuck am I working for this guy? He’s a twat”. And then you lose a chef. And you don’t gain anything. I definitely switched my management style up, and I listen to people more.

JB: You have plans to expand already…

TS: I was in New York a couple of weeks ago, looking at a site. So that will throw a spanner in the works. Never get comfortable. I’ve always wanted to challenge myself — to throw myself in the deep end. I didn’t go about things in the most normal way. I just took opportunities. And if it didn’t work for me, it didn’t work for me. And I moved on. So New York it is. I have a great following in the US, so it’s the logical next step. And the restaurant scene is buzzing. That one should be open early next year. The sites are bigger. The rents are extortionate. We might call it Straker’s. But my dream is to make two or three brands that we can take and put into cities around the world. America is the one for me. There’s huge growth potential over there.

“I’m four times as productive when I’m not drinking. I love the combination of food and drink, so I find it tough to give it up entirely”

JB: What’s the butter thing about?

TS: The first video I ever put up on TikTok got four million views, and I got 100,000 followers overnight. Then I posted my old videos, but nothing went viral like that. I did a butter video, and it did really well, and it just seemed like TikTok liked butter. So I thought, let’s do butter. I did a chicken skin butter and it got 10 million views. I did a burnt butter and it got 20 million. It went crazy, and the uptick in following was mad. It boosted my profile, and catapulted my growth.

JB: And now you make your own butter…

TS: We sourced an amazing dairy farm in Somerset, and they make some great butters – it’s all grass-fed and organic. The butter market in the UK is £1.5 billion a year. But if you look at the shelves in the supermarket, it’s all gold and silver, it’s boring. So as it stands, we are the largest butter company on Instagram in the UK, with Lurpak being the second. And we don’t even have a product yet. The packaging is completely different. It’s a little market disruptor. I’ve done two posts about it and we’ve got 15,000 followers already. I ordered my first two tonnes of butter the other day: that’s 8,000 blocks. We’ll do an online shop for proof of concept, then go into retail.

JB: Is it difficult juggling all of these projects with a young family?

TS: I make it up for breakfast every day. At 6.30am she wakes up, the older one. We fit in a walk before going to work, and sometimes they come in for dinner after school. I try to take Sundays off, but it doesn’t always work. It’s difficult. I went away recently for four days with the family. And I was basically asleep for two days, catching up.

JB: What do your friends and family think of your social-media fame?

TS: They find it amusing. But I haven’t bothered myself with their opinion too much. My mum was like, you’re a dick. She was concerned about me at one point — that I was partying too much. She had told one of my friends that she was going to come into the restaurant and drag me out by my collar and send me to rehab. Good luck. But that’s a motherly instinct.

JB: Is the partying side of things important, somehow, to the creative part?

TS: I think it’s detrimental to everything. If you’re hungover, you’re not productive. I’m four times as productive when I’m not drinking. I love the combination of food and drink, so I find it tough to give it up entirely. But when I work on a new project, I stay laser-focused and don’t drink, and stay fit and healthy. Because that’s what it takes to get these projects off the ground and over the line. You’ve got to raise money and look presentable and think of the ideas and do the design. So sobriety for work is good.

JB: What advice do you have for those who don’t necessarily know what they want to do with their lives?

TS: You’ve got to be prepared to make mistakes, and if you don’t like something, move on. You can’t be afraid. There’s so many things out there — so many different fields — and so many stories of people who find their dream job at 35. It’s never too late to go and do something. So you just need to take the time to make the mistakes. I didn’t know what I wanted to do until I was doing it. When I finally found something I wanted to do, I put my entire past life on hold and went for the future. And it’s been full sixth gear, going at it, ever since.

This feature was taken from Gentleman’s Journal’s Summer 2023 issue. Read more about it here…

Want more food content? These are London’s best special-occasion restaurants…

Become a Gentleman’s Journal member. Find out more here.

Become a Gentleman’s Journal Member?

Like the Gentleman’s Journal? Why not join the Clubhouse, a special kind of private club where members receive offers and experiences from hand-picked, premium brands. You will also receive invites to exclusive events, the quarterly print magazine delivered directly to your door and your own membership card.