Dafydd Jones’s empire state of mind

Dafydd Jones doesn’t particularly like parties – which seems, on the face of it, an odd admission for the most famous party photographer of his time. “But that’s probably why I’ve been able to keep it up for so long!” he smiles. “If you like parties too much in this job, that’s quite a bad look…” The schedule could certainly be gruelling. Hired by Tina Brown at Vanity Fair (and later deployed under Graydon Carter there, too), Jones was sometimes dispatched to shoot at more than 20 parties a week, scattered across the glossy rump of Manhattan. This was the city at its power-shouldered prime – the 1980s and 1990s, when greed was good and Brooklyn didn’t exist.

Jones had first come to prominence in London (a provincial backwater near Paris, one sometimes felt) with his revealing, artful, roisterous photos of the aristo party set and their various hangers-on – first in Oxford, where Boris Johnson et al. carried on like they already ran the place, and then in the capital, where the Sloane Rangers cavorted and snorted like the ponies in their stables. Tina Brown, who had made Tatler great again in the early 1980s and was doing something similar with Vanity Fair in New York, shipped Jones over to apply his sharp, observational lens. (Graydon Carter, in his foreword to this wonderful new book, writes how Jones was often like “a sniper”, “fading into the background”, shooting his subjects “without them knowing it” and returning with images that were “exuberant or just plain lethal”.)

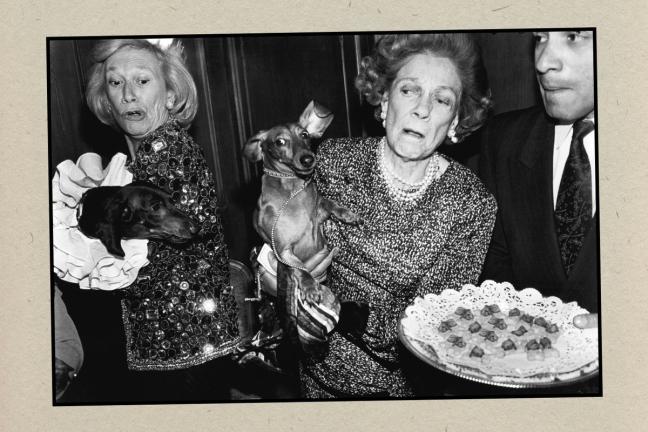

Jones arrived in New York, in 1988, with his wife and two young children in tow, and almost instantly discovered a party scene navigating a subtle but rumbling shift – the fading of the swannish, WASPy period of Upper East Side parties and aristocratic charity galas, and the beginning of a new era of celebrity and tabloid clout. That friction produces plenty of light and heat in Jones’s images from the time: on the one hand, the glorious shot of Brooke Astor and Iris Love’s silky dachshunds squabbling over silver-plattered canapés; on the other, Johnny Depp and Kate Moss smoking moodily at a book party in Moss’s honour, their gorgeous, troubled cheekbones sharp against the paparazzi flashes.

The New York magazine world was undergoing a vast, slow change, too. At the beginning, Jones could barely believe the scale and largesse of life in Vanity Fair’s offices in the early 1990s – a place with strict, almost militaristic hierarchies and thundering figures, where assistants had assistants and everyone had a town car on speed dial. Jones recalls teaming up on party assignments with Toby Young, who was mostly interested, for some reason, in the supermodel bashes that kicked off in the East Village at around midnight. This was just before Young wrote How to Lose Friends and Alienate People, his colourful romp about failing upwards (or perhaps succeeding downwards) through Manhattan’s power circles, of which Vanity Fair was then at the centre. “We both agreed that almost the most interesting story going on at that moment in time was inside the magazine itself,” says Jones of that world which placed such great importance on “where people sat when they had lunch in the Royalton Hotel”.

By the end of his time in the city, Jones sensed the writing was on the wall for this particular circus, even if everyone else was trying to pretend it wasn’t. He remembers at one point buying a giant personal computer in the mid-1990s, and carting it home with his kids in a red Radio Flyer wagon. “I couldn’t see how magazines could carry on,” he says.

Some images glow brighter now than they did at the time, perhaps on account of all the gathering darkness. Donald Trump pops up in the book with the flared inevitability of a cold sore, his stubby, jabbing fingers and pushy mannerisms instantly recognisable even in a frozen still-frame. “He wasn’t someone you’d expect to become the President of America,” Jones says now with deft understatement, noting how Trump would turn up at all sorts of “cheesy events”, far away from the apparent circle of power at the time.

At one such bash, Jones spotted a “wolf-like” figure looking out over the party from a balcony. “I took a portrait of him, just because he looked so strange,” Jones says. “I had a slight chill – he gave me a creepy feeling.” (Party photography is a sort of “talent-spotting” in some way, Jones says. You are looking for the people who stand out, even if you’re not quite sure why.) Jones approached the man later, and was handed a business card bearing the name Jeffrey Epstein. Just out of shot, by Epstein’s elbow, was Donald Trump.

One of Jones’s final assignments in the city was at the launch of Talk magazine – Tina Brown’s post-Vanity Fair venture, which would implode catastrophically three years later – in New York Harbor in September, 1999. “There was a beautiful late evening light during the boat trip, illuminating the Twin Towers behind us,” Jones writes in his introduction to the book. “There is a happy but now sad celebratory picture of Paul Newman, Natasha Richardson and Lauren Bacall enjoying the boat journey and anticipating the party ahead. The end of the nineties was when my time in New York came to an end.” There’s something painfully bittersweet in that off-hand “party ahead.” Looking at the photo now, it is hard not to reflect on just how many other things were about to come to an end, too.

- New York: High Life/Low Life by Dafydd Jones is published by ACC Art Books

This feature was taken from our Summer 2024 issue. Read more about it here.

Want more literature? These are the books we’re reading this year…

Become a Gentleman’s Journal Member?

Like the Gentleman’s Journal? Why not join the Clubhouse, a special kind of private club where members receive offers and experiences from hand-picked, premium brands. You will also receive invites to exclusive events, the quarterly print magazine delivered directly to your door and your own membership card.